Noah’s Ark – and Ours

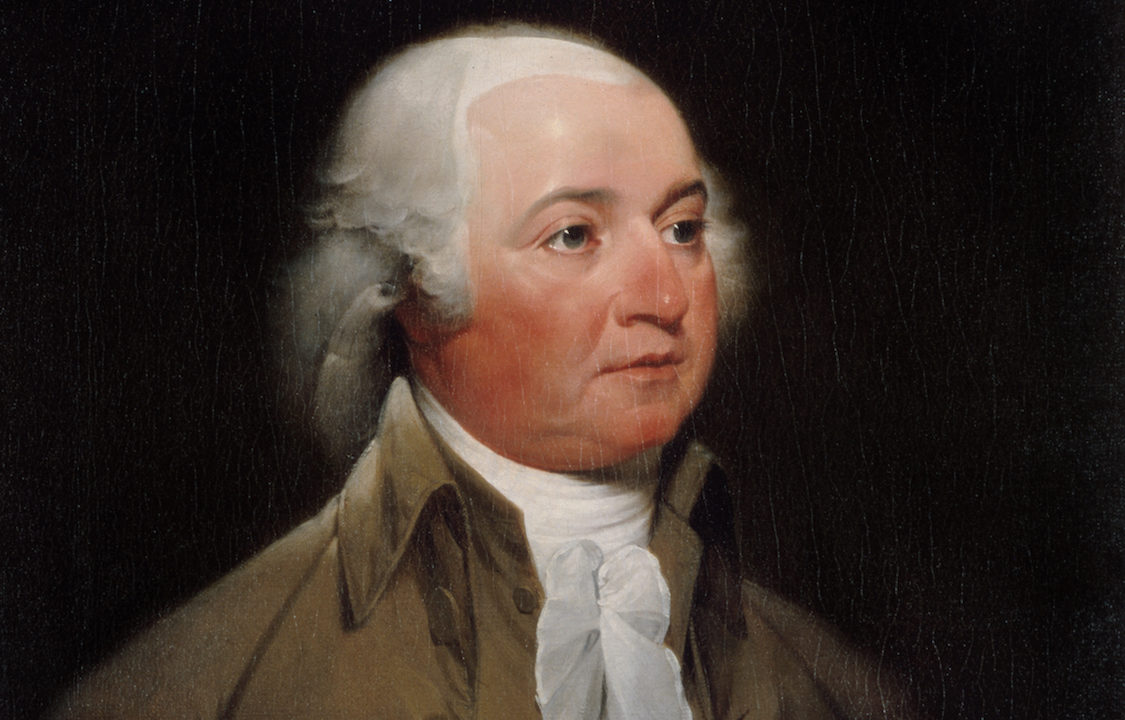

John Adams, who thought so highly of the Jews, was fondly recalled by Jews who reciprocated his admiration

John Adams was certain he would be forgotten. “The History of our Revolution,” he fretted to Benjamin Rush, “will be one continued Lye from one End to the other. The Essence of the whole will be that Dr Franklins electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod—and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War.”

Adams would thus certainly have been surprised had he been in Israel’s Knesset when the parliament welcomed Mike Pence, his successor as vice president of the United States. Prime Minister Netanyahu, in delivering words of greeting, spoke of the history of America’s support for the Jewish state. He then quoted words that Adams had written in 1819, long before Zionism had emerged as a movement: “I really wish the Jews again in Judea an independent nation.” Isaac Herzog, the leader of the opposition, then rose to deliver prepared remarks and cited the same quote. The vice president then himself made mention of John Adams’s affinity for the Jewish people, in a speech where Pence celebrated the miracle that was the State of Israel. Suddenly the man who worried so about his legacy was receiving the attention he had so ardently believed he deserved.

This is fitting. If any founder deserves to be celebrated in Israel, it is Adams. Thomas Jefferson thought little of the Jewish intellectual legacy. But the Jews were “the most glorious nation that ever inhabited this Earth,” Adams insisted. “The Romans and their Empire were but a Bauble in comparison of the Jews. They have given religion to three quarters of the Globe and have influenced the affairs of Mankind more, and more happily, than any other Nation ancient or modern.” Yet few in the auditorium knew the context of Adams’s declaration, noted by Netanyahu, in support of a Jewish restoration in the Holy Land; and this story lends special poignancy to Pence’s visit and to the ardently Zionist speech Pence himself delivered.

The words cited by Netanyahu had been written by Adams to the most prominent American Jew of his age: Mordecai Manuel Noah, a Jewish playwright, politician, and journalist. Speaking in 1818 to Congregation Shearith Israel in New York, Noah delivered a passionate paean to the nascent United States and to the home that Jews had found there. “Until the Jews can recover their ancient rights and dominions, and take their rank among the governments of the earth,” he declared, “this is their chosen country.” Yet Noah was convinced, half a century before Herzl, that the Jews could soon return to the Holy Land and create their own state: “Never were the prospects for the restoration of the Jewish nation to their ancient rights and dominion more brilliant than they are at present.”

Noah sent his speech, and his likeminded writings, to three past presidents: Adams, Jefferson, and Madison. While each responded politely, only Adams engaged the revolutionary proto-Zionist theme:

I could find it in my heart to wish that you had been at the head of a hundred thousand Israelites indeed as well disciplin’d as a French army—& marching with them into Judea & making a conquest of that country & restoring your nation to the dominion of it—For I really wish the Jews again in Judea an independent nation.

Several years later, Noah took steps to actualize his dreams, purchasing Grand Island near Buffalo, New York, to create a haven for persecuted Jews from all over the world. Naming it Ararat—where Noah’s ark had landed after the flood—Noah stressed that Jews finding refuge in America was only the first step to a Jewish restoration in the Holy Land. “In calling the Jews together under the protection of the American Constitution and its laws,” he pronounced, “it is proper for me to state that this asylum is temporary and provisionary. The Jews never should, and never will relinquish the just hope of retaining possession of their ancient heritage.” America, he argued, was a divinely ordained opportunity for the Jews of the world to seize control of their own destiny and proceed from there to the Land of Israel: “The time has emphatically arrived to do something calculated to benefit ourselves…and we must commence the work in a country free from ignoble prejudices and legal disqualifications.”

Prominently publicized by Noah, the plan was ridiculed by Western European Jewish leaders. No Jews came. Today, only the foundation stone Noah placed near Grand Island memorializes Ararat. Yet students of the story cannot fail to ponder what might have been. “Perhaps,” Robert Gordis once commented, “one cannot blame the leaders of West European Jewry for being hidebound by the political and religious conventions of their age. But they might have stimulated a mass Jewish exodus from Europe 50 years earlier, and saved untold lives from Hitler’s holocaust, had they possessed something of the grandiose vision of Noah.” There was, however, one man in America—John Adams—in sympathy with Noah’s vision, and this man had himself seen how nations can miraculously rise as a beacon of liberty to the world.

It is therefore fitting that Israel’s parliamentary leaders greeted a vice president of the United States by quoting Adams’s letter. This exchange between Adams and Noah, perhaps more than any other correspondence in American history, embodies the Jewish love affair with America and the philo-Semitism of some of its founders, which presaged the future American support for the Jewish state. For an Adams aficionado, the Knesset’s greeting to Pence was a sublime moment. John Adams, certain that he would vanish in the mists of memory, was suddenly cited and celebrated centuries later in a country on the other side of the world. John Adams, who thought so highly of the Jews, was fondly recalled by Jews who reciprocated his admiration. John Adams, who believed, when few did, that the Jews could one day be restored to Judea as an independent nation, was suddenly remembered in a Judea where the Jews had done just that.

On July 4, 1826, John Adams passed away, uttering three last words: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” Yet Jefferson had died several hours before. Both founders left the world together, on the 50th anniversary of American independence—providing providential proof, as Daniel Webster suggested, that “our country and its benefactors are objects of God’s care.” Adams’s words, however, were true. Jefferson’s legacy of liberty does survive, and Adams, his own fears notwithstanding, also lives on. Few events in recent history reified Adams’s immortality more than a Knesset quoting the man who had longed to see its own creation. John Adams indeed survives, and among the founders he would be the least surprised to learn that am Yisrael chai—that the Jewish people thrives as well.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

John Adams thought fondly of the Jews and they thought fondly of him.

John Adams thought fondly of the Jews and they thought fondly of him.