The Shame of Josh Shapiro

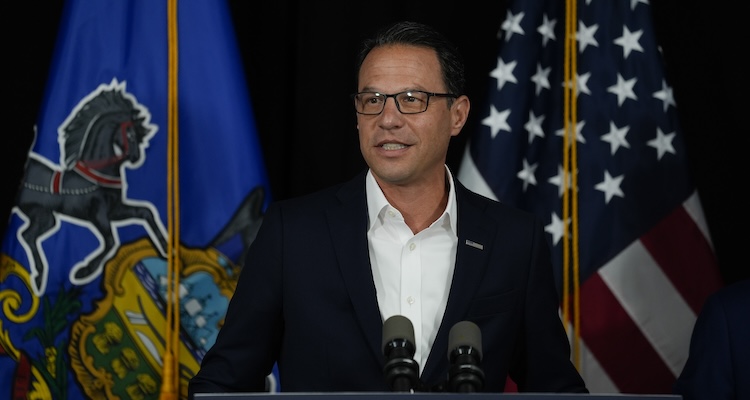

Governor Shapiro was faced with an opportunity to make American Jews proud, but he historically and tragically whiffed.

In her brilliant biography of Sandy Koufax, Jane Leavy described the day, indelible in so many American Jewish memories, that her subject refused to pitch in a World Series game that fell on Yom Kippur. Another great Dodgers pitcher, Don Drysdale, pitched in place of Koufax—and got slaughtered. The Dodgers were many runs behind when the manager, Walter Alston, walked to the mound to relieve Drysdale. “Hey skip,” Drysdale said. “Bet you wish I was Jewish today too.” In so doing, Drysdale reflected his respect for the decision Koufax had made. Leavy observes that for Jewish Dodgers fans, the “loss was a win.” And indeed it was. Koufax had shown that the spotlight of the series mattered less than denying something central to his identity as a Jew; and in the process, he taught American Jews to act likewise.

It is with this in mind that we can study the sad saga of Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro. What it portends for the future of American politics, and the place of Jews within it, will be judged by many factors, including the course ultimately taken by the political party of which he is a part. But in the annals of Jewish history, one tragedy can already be marked in the life of this undeniably talented, and proudly Jewish, political figure. He was faced with an opportunity to define himself in the minds of American Jews, and he historically and tragically whiffed.

With Shapiro widely reported to be the leading candidate to serve on Kamala Harris’s ticket, someone clearly seeking to damage his candidacy dug up an op-ed from Shapiro’s college days in which he expressed his doubts that the Oslo peace process would succeed. Leaving aside the prescience of this prediction, Shapiro actually concluded the article by stressing that he genuinely hoped that peace would arrive in the Middle East. But it was the language he utilized in this final sentence that so many of his political enemies seized upon. “Despite my skepticism as a Jew,” Shapiro wrote, “and a past volunteer in the Israeli army, I strongly hope and pray that this ‘peace plan’ will be successful.”

The Israeli army? Had Shapiro served in the IDF? We are given to understand that he did not, that he merely volunteered on an Israeli base in a nonmilitary capacity. But Shapiro was clearly once proud enough of his volunteer work that he considered it a form of participation in the IDF; and it is not at all obvious that he was wrong to have done so. The Talmud stresses that when the Jewish people go to war against our enemies, those not serving in battle can still laudably play a role by providing “water and food” to the troops and repairing the roads on which the soldiers travel. The 1990s version of Josh Shapiro clearly believed that assisting Jews on the other side of the world in facing the many enemies that surrounded them was a source of pride—and that version of Josh Shapiro was correct.

But in 2024, it appeared that if Shapiro were to embrace his identity as “a past volunteer in the Israeli army,” his viability for the Democratic ticket would be forfeit, and therefore a spokesman, Manuel Bonder, was directed to deliver a statement to the media to redefine the past: “While he was in high school, Josh Shapiro was required to do a service project, which he and several classmates completed through a program that took them to a kibbutz in Israel where he worked on a farm and at a fishery. The program also included volunteering on service projects on an Israeli army base. At no time was he engaged in any military activities.”

As a form of public relations, Bonder’s statement is, in a way, a mesmerizing, mealy-mouthed masterpiece. First, without addressing his earlier description of his volunteerism, the statement stresses that Shapiro did not volunteer for the IDF at all and did not consider himself to have done so. Moreover, the statement emphasized that his time on the base had been merely one of a myriad of activities, including work on a “farm and a fishery” in a kibbutz. The IDF base, in other words, was but a blip. And most brilliantly, and perversely, the statement stressed that all of this occurred because, “while in high school,” Shapiro had been “required to do a service project.” The implication is clear: Had he not been a minor, devoid of autonomy and burdened by a pesky volunteerism obligation, he might never have gone to Israel in the first place.

I am envious of Josh Shapiro, in that I never merited, as a young man, to volunteer on an Israeli army base, and I played no such personal role in helping to support the Jewish state. And I believe that, in his heart of hearts, Governor Shapiro remains proud of it, as well. But we cannot ignore the impact of how he addressed the matter—the implied shame of his affiliation, however small, with the IDF. There are any number of American Jews from walks of life similar to Shapiro’s who are now in their teens and twenties and who will well note what has occurred. Some of them may aspire to a career in politics and will now be all the more incentivized to abstain from volunteering in Israel—not only for the IDF, but in any way.

It is to these Jewish men and women that Shapiro could have spoken, in an alternate version of events. Imagine if he had met the moment. Imagine if he had spoken of his memories of the Israeli base, and of the impact that it had on him. Imagine if the Josh Shapiro of the 1990s had suddenly appeared, and the governor spoke of the integrity of the IDF and its compassion for civilian life when contrasted with so many other armies on earth. Such a response would have affected many Jewish Americans for years and earned him a genuine legacy in Jewish history. It might have lost him the nomination for the vice presidency, but in the end, that loss would have been a win. In the meantime, we can look to John Fetterman when we seek a Pennsylvania politician who proudly and publicly supports Israel’s Defense Forces as they battle the forces of terror; and I can certainly say, in the words of a great Dodgers pitcher, that I wish he were Jewish today, too.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

Governor Shapiro was faced with an opportunity to make American Jews proud, but he historically and tragically whiffed.

Governor Shapiro was faced with an opportunity to make American Jews proud, but he historically and tragically whiffed.