Fear and Joy in Sepharad and Ashkenaz

What happens when an Ashkenazi rabbi leads a Sephardi synagogue during the Days of Awe? A profound encounter with new moods in Jewish life.

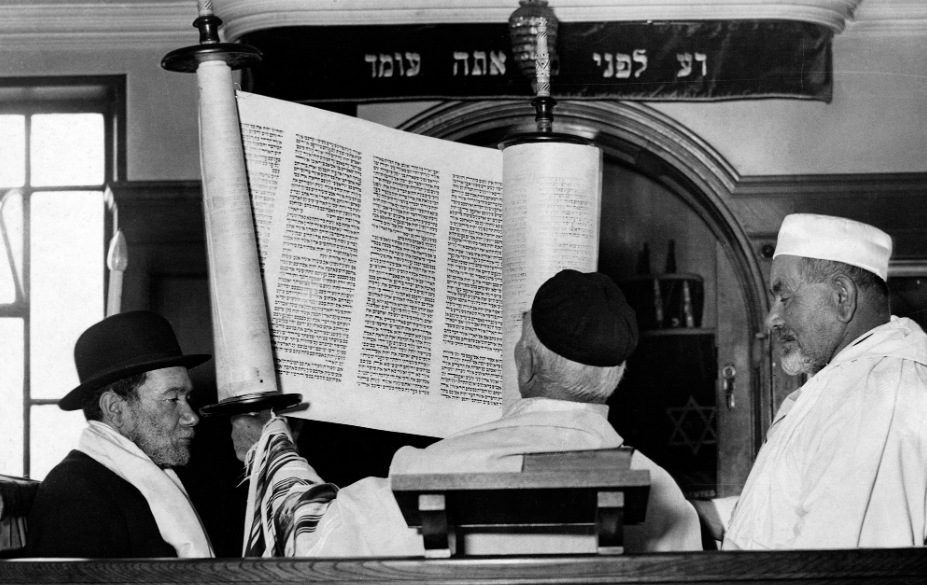

On a day of indelible memories, it was one that stood out. In 2013, I was privileged to be inducted as the rabbi and minister of Congregation Shearith Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in America. Shearith Israel has long been known as the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York, reflecting the unique liturgical traditions that its diverse membership has long preserved. About the storied history of the congregation—America’s oldest, featuring Jewish patriots who had encountered Washington, Hamilton, and other founders—I knew a great deal. I also knew that I faced a steep learning curve when it came to assuming the responsibilities of leading Shearith Israel in prayer. For this congregation’s minhag, its customs of prayer and worship, its magnificent liturgy, are above all rooted in the traditions of Spanish and Portuguese Jewry, on the civilization and culture known as Sepharad.

As one who had grown up within the Ashkenazi tradition, many of the liturgical traditions of the synagogue were new to me, and to many of the guests attending the installation that day. One prominent Jewish intellectual was in the audience, and, as I approached him to express my gratitude for his attendance, he quipped that he did not understand how I could embrace a tradition that “didn’t say Un’taneh Tokef.”

Since then, it has been twelve years that I have merited to minister at my congregation, and when I am asked to describe what it was like for one steeped in the Ashkenazi tradition to take on my particular pulpit, as I regularly am, it is to this moment that I turn. While the tunes at Shearith Israel used for the prayers during the week and Shabbat are different from those with which I was raised, the words are to a great extent the same, as those prayers were established in earlier periods of rabbinic Judaism. Instead, it is the High Holy Days where the liturgical differences make themselves most known—and in a profound, indelible, unforgettable way. It is not only the words and melodies of the piyyutim—the compositions created for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur that are recited by Sephardi Jewry—that are different from those of the Ashkenazi world. It is that the very mood they conjure and create is fundamentally different.

In the last decade, these Sephardi prayers, of whose existence I had previously had nary a notion, have become an indelible part of my experience of the Days of Awe. And today, I myself open Yom Kippur—or as it is simply known at the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, Kippur—by leading Kol Nidrei, and bring it to a close by leading the Ne’ilah prayer, with very different tunes, than those with which I was raised. Of course, the memories of High Holy Days past, especially those experienced at my father’s side as a child, remain indelible as well, so that, in a sense, the two very different ways to experience these days of days are both very much alive in my mind. There is no longer, for me, a singular High Holy Day experience.

That, perhaps, is for the best. For this past decade has exposed me to new dimensions of the richness of Jewish tradition, and the different sounds, sights, emotions that it offers. And as Jews bid farewell to a year that has been unlike any other in recent memory, it is, in my view, the taking of both liturgical perspectives in tandem that can best capture our feelings as we pray for the year ahead.

What happens when an Ashkenazi rabbi leads a Sephardi synagogue during the Days of Awe? A profound encounter with new moods in Jewish life.

What happens when an Ashkenazi rabbi leads a Sephardi synagogue during the Days of Awe? A profound encounter with new moods in Jewish life.