Hamilton’s Hallmark

The university hall that was ransacked by an anti-Semitic mob was named for a founding father who uniquely understood the role of Jews in America.

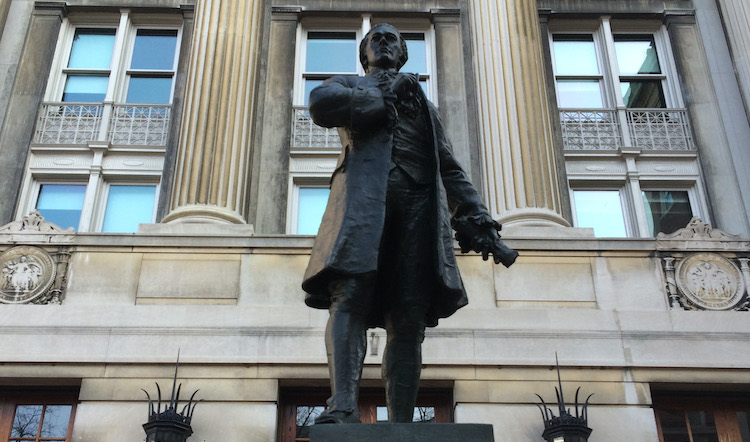

As a mob of Columbia students and other anti-Semitic agitators violently entered and occupied the University’s Hamilton Hall, only to be valorized by members of the media and the academy, my thoughts turned to the man for whom the building was named. Alexander Hamilton had overseen the transformation of the institution once known by the royalist name “King’s College” into the American institution called Columbia, and he had also placed a Jew—the New York spiritual leader Gershom Mendes Seixas—on Columbia’s board. This was the first time in the history of the West that a Jew was so honored, a sign of how Hamilton understood the uniqueness of America and the place of the Jews within it. Hamilton would vindicate this worldview in a moment in a New York court case that has long since been forgotten, but that deserves to be remembered in the season in which we find ourselves.

The tale is told by the historian Andrew Porwancher in his remarkable work, The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton. After leaving George Washington’s government, Hamilton earned a livelihood by returning to his legal practice in New York. One of his clients was a local merchant by the name of Louis LeGuen, whose case had worked its way through New York’s legal system and was heard by the State’s “Court of Errors.” This, as Porwancher tells us, was no ordinary court; it was a large tribunal that included not only judges but prominent politicians, including the president of the state senate.

The legal teams on both sides included some of the most famous names of American history. Hamilton was joined by Aaron Burr in representing LeGuen. Opposing them was another father of the American Constitution, Gouverneur Morris. Given that several witnesses for LeGuen were Jewish, Morris chose to focus on the veracity of their testimony. As Porwancher tells us, this was a reaction to the mellifluence of the lawyer on the opposing side:

After Hamilton delivered a forceful closing argument spanning six hours, Morris knew he could not compete with Hamilton on legal grounds. Instead, Morris told the court that he had no intention of referencing law books and alternatively would “appeal to the principles written on the heart of man.” Morris’s flowery address soon degenerated into a base attack on Hamilton’s two witnesses of the Jewish faith. Alluding to them as “these Jew witnesses,” Morris sought to impugn their credibility on the basis of their religion. “Jews are not to be believed upon oath,” he insisted bluntly.

Thus did Morris adopt a strategy that was abhorrent but not insensible: to act on the assumption that anti-Semitism was very potent and that the “heart of man” was vulnerable to it.

There is, of course, enormous irony to this, given that Morris had been the one who had suggested that the Constitution begin with the three words “We the people,” an enduring and eloquent expression of democratic equality. Hamilton, as Porwancher tells us, had already delivered his own argument but chose to speak again—and to respond to the anti-Semitic allegation, attempting in his own way to address the heart of man. One might even suggest that Hamilton sought to influence what another great American would later call the “better angels of our nature.”

What is remarkable about Hamilton’s response is that it not only denounced Morris’s bigotry; it also made a case for American philo-Semitism. Hamilton utilized language that was less legal than theological, asking the tribunal about Morris: “Has he forgotten, what this race once were, when, under the immediate government of God himself, they were selected as the witnesses of his miracles, and charged with the spirit of prophecy?” It was, in other words, the Jews who served as the medium of the very scripture that had inspired American republican government, and who observed that “pure and holy, happy and Heaven-approved faith.” Hamilton further linked Jewish suffering to the destruction of Jerusalem, referring to the Jews as “the degraded, persecuted, reviled subjects of Rome…in all her resistless power, and pride, and pagan pomp.” As Porwancher puts it, Hamilton not only emphasized the equality of all before the law; he also stressed that Morris was “perpetuating a dark history of antisemitism that had plagued Jews since antiquity.”

It goes without saying that one cannot imagine this speech being given in Europe at this particular time. And it deserves to be remembered along with Washington’s correspondence with American Jewry as reflecting the unique way in which Jews were embraced in this nascent nation. But as impressive as Hamilton’s rhetoric was, the result was equally important: The court embraced Hamilton’s position by a vote of 28–6, signifying that the anti-Semitism that truly had marked the hearts of so many men would be so remarkably absent in the hearts of so many Americans then and in the years to follow.

We can now find a deeper meaning to the fact that the Columbia mob chose to vent its anti-Semitism on an edifice named for, and featuring a statue of, Alexander Hamilton. These hoodlums had chosen a target that allowed their assault to serve as a metaphor for the political battle that now faces us: between those Americans who understand the profound connection between the American republic and the Jewish story, and those who are all too eager to revive an age-old bigotry and to give it new power in a land where, thank God, it has so rarely had purchase.

To watch scenes from Columbia, and to witness the utter failure of its administration, is to recall another passage from Porwancher’s book, describing Hamilton’s education before the Revolution and the qualifications that Hamilton himself would later seek in choosing Columbia’s president:

A King’s College education was intended to impart not just know-ledge but virtue, and to that end the college banned all sorts of juvenile buffoonery. During Hamilton’s time, the college president made use of a notorious “Black Book” that recorded indiscretions. Transgressive behavior ranged from the predictable (skipping classes) to the mischievous (teacup theft) to the downright unseemly (cockfighting). Punishment often entailed paying a fine or translating Latin texts. In his later capacity as a trustee of the college, Hamilton would advise with moderation that a college president should “be of a disposition to maintain discipline without undue austerity.”

Needless to say, the University that was essentially founded by a Founding Father does not now have such a president. It is, sadly, too much to hope that Columbia’s administration will soon again become worthy of Hamilton’s legacy, but there is every indication that many millions of Americans still embrace the perspective to which Hamilton, in that New York court, gave eloquent voice. May the rediscovery of this story allow Hamilton’s words to become a clarion call in our hearts.

The university hall that was ransacked by an anti-Semitic mob was named for a founding father who uniquely understood the role of Jews in America.

The university hall that was ransacked by an anti-Semitic mob was named for a founding father who uniquely understood the role of Jews in America.