How Soloveitchik Saw Interreligious Dialogue

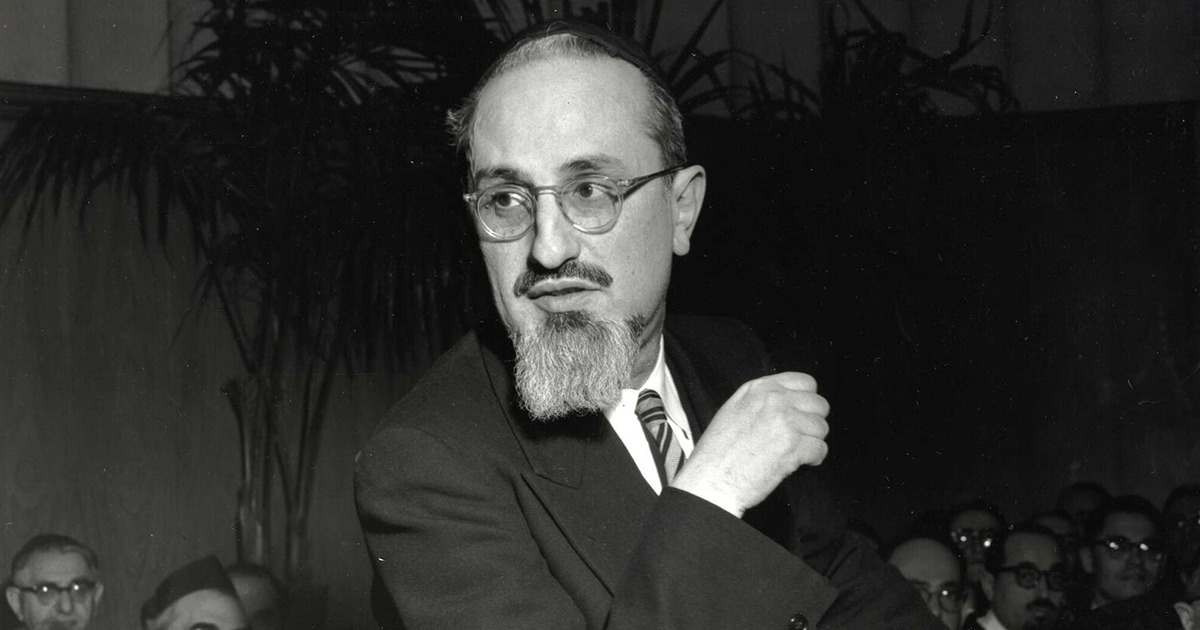

On the potential benefits and necessary boundaries of interfaith dialogue, as understood by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

In September 2000, a Baltimore-based institute for interfaith dialogue issued a statement titled “Dabru Emet: A Jewish Statement on Christians and Christianity.” The statement enumerated a series of theological beliefs shared by Jews and Christians, and insisted that such a statement was essential given the dramatic change during the last four decades in Christian attitudes toward Judaism. Signed by over 170 rabbis and Jewish studies professors, “Dabru Emet” — Hebrew for “speak the truth” — received much publicity in the media and was published as an ad in The New York Times. One feature of the statement, however, went largely unnoticed: While “Dabru Emet” had numerous rabbinical signatories, it had a paucity of Orthodox ones.

The reluctance of Orthodox rabbis, even those rabbis who have a history of communication with the Christian community, to sign the declaration reflects a strict adherence to the admonitions of the revered Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, known by his students and followers as “the Rav,” who in the 1960s prohibited theological dialogue with the Catholic Church. With the 10th anniversary of the Rav’s passing being widely commemorated this Passover, reflection is warranted on the limits that the Rav’s prohibition still places on Orthodox Jews today — as well as on opportunities for dialogue yet to come.

The Rav’s opposition to communal, and organizational interfaith dialogue was partly predicated upon the prediction that in our search for common ground — a shared theological language — Jews and Christians might each sacrifice our insistence on the absolute and exclusive truth of our respective faiths, blurring the deep divide between our respective dogmas. In an essay titled “Confrontation,” Rabbi Soloveitchik argued that a community’s faith is an intimate, and often incommunicable affair. Furthermore, a faith by definition insists “that its system of dogmas, doctrines and values is best fitted for the attainment of the ultimate good.” In his essay, the Rav warned that sacrificing the exclusive nature of religious truth in the name of dialogue would help neither Jews nor Christians. Any “equalization of dogmatic certitudes, and waiving of eschatological claims, spell the end of the vibrant and great faith experiences of any religious community,” he wrote.

Interestingly, when one reads the writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel, one of the most influential and enthusiastic proponents of interfaith engagement at the time that the Rav first voiced his opposition, we find an example of the equalization of dogma that the Rav so opposed. In his essay “No Religion is an Island,” Heschel noted that religions have profound disagreements, and each claim to be true. Yet he argued that truth is not exclusive, that “ultimate truth is not capable of being fully and adequately expressed in concepts and words,” and that God speaks to man “in a multiplicity of languages. One truth comes to expression in many ways of understanding.”

Orthodoxy rejects this approach. While Jews and Christians both agree on many religious issues, we disagree, and believe each other profoundly wrong, about others. Either Jesus is the son of God, or he is not. Religious relativism is not the answer to disagreement between faiths; yet relativism, and a blurring of religious distinctions, all too often result when two deeply believing faith communities engage each other in the public arena on theological issues.

Many, however, misunderstand the limits of the Rav’s prohibition. Some Jews believe that he forbade any engagement of other faiths, and all too many Christians assume that our reluctance to engage in theological dialogue indicates a disinterest on the part of Orthodoxy in the concerns of much of America’s population. For example, the influential Catholic Father Richard John Neuhaus recently fretted in the journal First Things that in contrast to those who refuse to engage the Christian community in dialogue, the authors of “Dabru Emet” seem willing to explore “a promising relationship to the majority religion and culture.”

Overlooked in the debate is that in issuing a set of guidelines to Orthodoxy’s Rabbinical Council of America, titled “On Interfaith Relationships,” the Rav did not ban all Orthodox interfaith engagements. When it came to causes that were not strictly theological in nature, the Rav insisted that there was much that Orthodoxy and Christianity could accomplish together. All human beings, he believed, are charged by the Almighty to enhance the physical and moral welfare of humanity. In seeking the moral betterment of man, specific religious beliefs of Jews and Christians serve to unite rather than divide us.

The Rav stressed that the two faiths can dialogue not only on such topics as “war and peace, poverty, freedom” but also on “the threat of secularism.” This interfaith engagement, he stressed, will be based on “our religious outlooks,” in which we express our feelings “in a peculiar language which quite often is incomprehensible to the secularist,” and in which we define “morality as an act of Imitatio Dei” — of imitation of the Almighty. While organizational dialogue on dogma was prohibited, The Rav insisted that Jews and Christians can, and should, dialogue on the distinctly religious morality that they share.

We live in an age in which the biblical-moral traditions that have guided us for centuries are increasingly being forgotten. Orthodoxy now shares certain moral commonalities with some Christians that it does not share with other Jewish denominations, such as certain views on abortion and homosexuality. While most Orthodox rabbis rightly refrained from signing “Dabru Emet,” we Orthodox ought to issue a statement of our own, one focusing not on theology, but on morality. It would let the Christian community know that we will work with them to preserve and protect, inter alia, the sanctity of life and of marriage in America, and that Orthodoxy is uniquely suited to join them in this endeavor.

While the Rav rightly feared religious relativism, and therefore forbade communal theological engagement, the effort to enhance the welfare of the world, as well as the battle to preserve the biblical-moral tradition in America, provide common cause for traditional Jewish and Christian believers. While our particular faiths divide us, it is also our faith — specifically, our adherence to traditional religious mores — that unites us and provides a foundation for dialogue in the future.

This article was originally published at the Forward.

On the potential benefits and necessary boundaries of interfaith dialogue.

On the potential benefits and necessary boundaries of interfaith dialogue.