Love and the Law

Christians are beginning to seek the secret of Jewish survival, and are discovering it in the Jewish love of the law.

One evening in 1663, the London socialite Samuel Pepys decided to check out London’s latest attraction: Jews, who had just been allowed back into England. Pepys sought out a typical synagogue service in order to get a sense of what was for him a foreign faith. Unbeknownst to Pepys, the evening he had selected to visit was Simhat Torah, when Jews celebrate completing the annual reading of the Mosaic Law with raucous dancing.

Pepys was bewildered by what he saw. “But, Lord!” he wrote in his diary, “to see the disorder, laughing, sporting, and no attention, but confusion in all their service, more like brutes than people knowing the true God, would make a man forswear ever seeing them more and indeed I never did see so much, or could have imagined there had been any religion in the whole world so absurdly performed as this.”

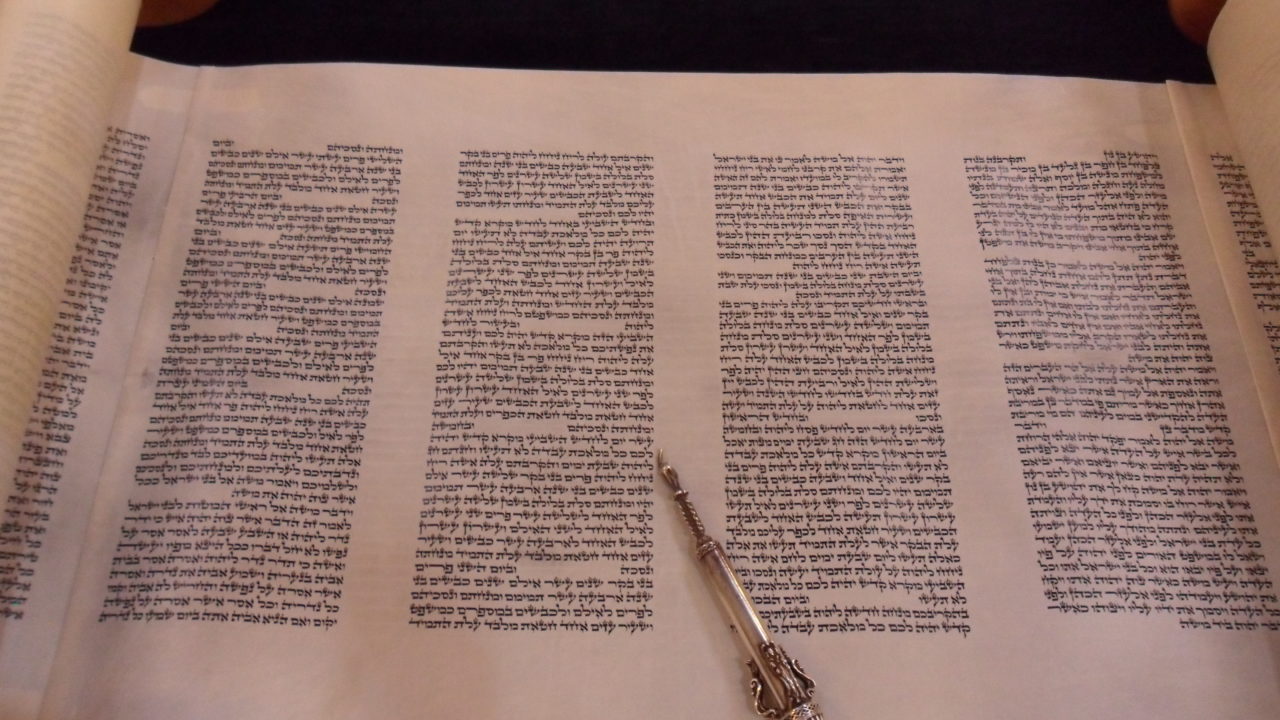

Pepys’s visit may have been ill-timed, but he did witness the soul of Judaism. For Jews, the law is the source of our most profound joy. And while Simchat Torah is a venerable tradition, the true celebration of the law is the holiday of Shavuot, marked by Jews this month as zeman matan torateinu, the time of the giving of the law. The Torah—a rigorous and complex code containing 613 commandments, to which the rabbis later added a myriad of further prohibitions and obligations—is for Jews an exquisite source of happiness, the ultimate embodiment of the Almighty’s love, and God’s greatest gift.

This may seem counterintuitive. Indeed, Christian thinkers have been startled by the fact that law—in all its multifarious details—can be a source of delight. In his Reflections on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis admits he was confounded by the Psalmist’s description of the Torah as sweeter than honey. “One can easily understand,” Lewis asserts, how laws may be important, even critical, but “it is very hard to find how they could be, so to speak, delicious, how they exhilarate.” Indeed, for one who overcomes his own desires in obedience to God’s commands, the law, Lewis write, “could be more aptly compared to the dentist’s forceps or the front line than to anything enjoyable or sweet.” Similarly, Soren Kierkegaard, reflecting Paul’s description of the Law as a “curse,” sees in the Torah an infinitude of obligations that can never be fulfilled: “A human being groans under the Law. Wherever he looks, he sees only requirement but never the boundary, alas, like someone who looks out over the ocean and sees wave after wave but never the boundary.”

In the past two decades, however, a stunning new genre of religious writing has appeared: Christian appreciation of the Jewish love of the law. These sensitive reflections are instructive not only to Christians but also, in certain ways, very interesting to Jews, as we can learn a great deal when we see ourselves through an outsider’s insightful eyes.

One such appreciation was written by Maria Johnson, a Catholic theologian at the University of Scranton. In her 2006 book, Strangers and Neighbors, Johnson describes visiting an Orthodox Jewish home on a Shabbat afternoon. Superficially, the Jewish Sabbath presents us with Judaism at its most didactic—a collection of melakhot, forbidden forms of work that cannot be performed—and Johnson had assumed that it was, for her friends, “a 25-hour prison of petty regulation.” Then, Johnson experiences the peace that pervades the Jewish home on this day, and in a jolt of realization understands “why my friends spoke of it with such love, why they thought of the day not as a prison but as a queen.” Johnson muses that in an age of almost infinite distractions, the rigidity of the laws actually frees families to focus on what is most important: “All the laws, the 39 acts that generations of rabbis have multiplied into hundreds of prohibitions on the most trivial everyday activities, are an adamantine edge to chisel holiness into the week in a way that cannot be ignored or evaded by distraction and must therefore be welcomed and embraced and celebrated.” Rather than an encumbrance, the law liberates by ensuring that there is no way to do anything except, as Johnson writes, “experience time as creatures whom God has made in his own image and blessed and chosen and called.”

Johnson here emphasizes the external impact of the law on the Jewish experience. Another Christian intellectual has written insightfully on how a lifetime of obedience to the Torah transforms Jews internally. In an essay titled “Loving the Law,” the Catholic theologian R.R. Reno meditates on the writings of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik. He reflects that while Christianity has given in all too often to the Gnostic temptation to reject this world, Jewish law insists that the soul is formed in the real world through habit-forming activity. The logic, Reno writes, is straightforward: “When our imperatives become the intentions and actions of those whom we command, then we begin to enter into communion with them.” Reno compares this to a child who obeys his father’s command to do his homework and ultimately comes to value education. “Soloveichik has helped me,” Reno writes, in seeing how law is a precious gift. While Kierkegaard describes the Torah as a burdensome endless obligation, Reno argues that Jewish laws “are as countless arrows of love shot downward and into human life,” so that the more expansive and detailed the law, the more completely is one’s life “penetrated by the divine.”

Christians, then, describe how the Torah sanctifies the external and molds the internal; it makes the Jewish home holy while creating the Jewish character. Both themes are combined in another remarkable example of a Christian appreciation of the law. In 2012, Philadelphia’s Archbishop Charles Chaput visited the beit midrash, or study hall, of Yeshiva University, where he encountered hundreds of young men engaged in Talmud study. Then, in a Church homily, he delivered a paean to what he had witnessed. He was struck, Chaput told those assembled in Church that Sunday, by the passion the students had for the Torah: “They didn’t merely study it; they consumed it. Or maybe it would be better to say that God’s Word consumed them,” forming friendship between themselves, and beyond themselves, with God. Chaput then reflected how the Torah was the source of Jewish immortality:

I saw in the lives of those Jewish students the incredible durability of God’s promises and God’s Word. Despite centuries of persecution, exile, dispersion, and even apostasy, the Jewish people continue to exist because their covenant with God is alive and permanent. God’s Word is the organizing principle of their identity. It’s the foundation and glue of their relationship with one another, with their past, and with their future. And the more faithful they are to God’s Word, the more certain they can be of their survival.

With words that one once could never have imagined being uttered in a homily in a Roman Catholic Church, Chaput then adds: “What I saw at Yeshiva should also apply to every Christian believer, but especially to those of us who are priests and bishops.” His reflections may reveal one reason why this new genre of Christian writing, unlike any other in two millennia, has suddenly emerged.

In an age of libertinism, Christians are coming to appreciate the role rigorous adherence to law plays in Jewish character formation—and in an age when Christians are now cultural outsiders, Christians are beginning to seek the secret of Jewish survival through the centuries, and are discovering it in the Jewish love of the law.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

When Christians seek the secret of Jewish survival.

When Christians seek the secret of Jewish survival.