Menachem Begin’s Covenantal Zionism

What Begin’s 1972 elegy for the diaspora reveals about a worldview unique among Israel’s founders.

This essay by Meir Soloveichik is, in part, a commentary on a speech that Menachem Begin gave in 1972. Mosaic published the first English translation of the speech in May 2020.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared Israeli independence. It is one of the most wondrous moments in Jewish history, worthy of religious reverence. And yet, reading the text of the declaration with religious sensitivities, it is hard not to notice something missing. The Israeli declaration of independence does not explicitly mention the divine. Secular Zionists, believing in the power of unassisted human will to make history, insisted that the God in Whom they could not believe be left out of it. Instead, the text concludes with a reference to Tsur Yisrael, the “Rock of Israel,” a traditional appellation for the Almighty, but a phrase which could also be interpreted as a reference to the flinty resolve of the IDF.

As for the Holocaust, no description was given of the Jews of the Diaspora who had just been murdered by the Nazis, no description was given of the lives they had lived, or of their faith. The Shoah was invoked in the declaration’s text, but only to justify the necessity of Israel’s founding:

The catastrophe which recently befell the Jewish people—the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe—was another clear demonstration of the urgency of solving the problem of its homelessness by re-establishing in the Land of Israel the Jewish state, which would open the gates of the homeland wide to every Jew and confer upon the Jewish people the status of a fully privileged member of the community of nations.

In addition to these, there was another absence on that Friday afternoon in Tel Aviv. One man who could be considered a founding father of Israel was not present at the ceremony. Menachem Begin was not present for several reasons. He was hated by David Ben-Gurion. But even if Ben-Gurion had felt differently, Begin would still not have been present at the ceremony because British rule over Palestine would not expire until midnight, and he was still the most wanted man in the region. It was only the next night, after Shabbat, that the leader of the Irgun emerged from hiding. Over the radio, he announced that his revolt was over, and that his organization was to become part of the national army. That radio address is noteworthy in its contrast to the words of the declaration, pronounced to the world the previous day.

Rather than eliding the existence of God, Begin began his address with the traditional sheheḥiyanu blessing, thanking God for allowing us to reach this momentous hour. Begin echoed the phrase Tsur Yisrael—the purposely ambiguous locution used in the declaration—but he enlarged it to acknowledge Tsur Yisrael v’Go’alo, the rock of Israel and its redeemer. No one could mistake his intention. Begin, the man whose parents had just been murdered by the Nazis, did not see the victims of the Shoah in political terms. To him, their memory should not be a proposition in an argument—even an argument about something as momentous as the state of Israel. The slain Jews of Europe carried moral integrity; they were beacons and polestars who lived alongside those who now fought for the Jewish people’s resurrection. That Saturday night, Begin said:

We shall be accompanied into battle by the spirit of the heroes of the gallows, the conquerors of death. And we shall be accompanied by the spirit of millions of our martyrs, our ancestors tortured and burned for their faith, our murdered fathers and butchered mothers, our murdered brothers and strangled children. And in this battle we shall break the enemy and bring salvation to our people, tried in the furnace of persecution, thirsting only for freedom, for righteousness, and for justice . . .”

When I teach political philosophy, I ask students to examine the differences between Begin’s speech and Israel’s declaration of independence. I note that Begin’s religious phrases do not necessarily mean that he led a life of rigorous observance of Jewish law. But the phrases do demonstrate that modern Zionism did not necessitate a rejection of the past. Modern Zionism should instead gratefully acknowledge its continuity with, and indebtedness to, all that had come before.

I call Begin’s worldview “covenantal Zionism,” which melds Jabotinsky’s worldview with an encompassing approach to Jewish history that differed profoundly from that of many other Zionist leaders. The covenant of Israel, Moses taught, embraces “those who are here today and those who are not here today” (Deuteronomy 29:15). One cannot live as a Jew if it is not in communion with past and posterity, and Menachem Begin rightly rejected the predilection of the Labor Zionist elite for amputating 2,000 years of exilic existence from Israeli identity. Begin understood that the battle for Jewish independence must be waged with a feeling of gratitude to those who had gone before, and especially to those who had been murdered, the Jews who died with dreams deferred.

Of all the speeches that Menachem Begin made in his career, nowhere is the unique, covenantal nature of his Zionism more manifest than in “We Were All Born in Jerusalem,” his elegy for his fellow Jews, the Jews of Brisk.

I remember when I first read it. I had been doing research at the Begin Center in Jerusalem, preparing for a year at Yeshiva University’s Straus Center in which we would be marking 100 years since Menachem Begin’s birth. There the staff found for me this 1972 speech, a eulogy for the Jews of the city led, coincidentally, by my own ancestors. I took a copy of his words to the nearby Inbar Hotel to read during lunch. I sat, and as I read it in the lobby restaurant, tears began to pour from my eyes; tears for my family, for my brethren, for Begin’s family, tears for the knowledge that the unique lives of faith that they personified would never be created again. Yet, through these tears I clearly saw the remarkable soul who could write and speak these words. I could not be prouder that my Straus Center colleague, and my student, have, in translating the speech, brought Menachem Begin’s poignant words to a wider audience.

In tribute to Begin, my hero, I offer a brief peirush, a commentary, on what are, for me, the most significant passages in the text. In the spirit of the speech, I will draw on the lives and the insights of the rabbis of Brisk, the very members of my family whom Begin names. I hope my understanding does justice to the man who, more than any other, inspired my thinking about what Zionism means.

Begin’s eulogy startsby describing the pride in his origins that unites him with all those who assembled that evening to mourn for their families:

Many Jews lived there, and Gentiles too. And the Jews had the custom of calling such a city “a city and mother of Israel.” The city was Brisk—not one of the largest cities in the world, but perhaps it was a mother, or a stepmother, to its Jews. We were all proud that this Brisk had a history: the legendary king chosen to rule for a day or two, and the towering geniuses of Torah, cedars of Lebanon. Who among us did not see ourselves as companions to Rabbi Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik [1820–1892], to [his son] Rabbi Chaimke [1853–1918], as if we had been with them all the days of our lives?

We have to pause to appreciate how remarkable this is. Here Begin makes reference to my ancestors: Rabbis Joseph Ber and Ḥayyim Soloveichik, leaders of the community of Brisk, known for their talmudic brilliance. Rabbi Ḥayyim was renowned for creating a way of studying Talmud for which Begin’s hometown would be known: the Brisker Method. These rabbis were also known for their fierce opposition to Zionism, a source of tension between the Soloveichiks and Begin’s father, a leader of the Zionists in Brisk. One might understand if, in 1972, looking back on his murdered parents, he would remember the rabbinic leadership with bitterness. But no: for him the Soloveichiks are a source of pride; indeed, he considers himself a shutaf, a partner, to their lives. Disagreeing with his childhood rabbis does not mean rejecting what they embodied. On the contrary, Begin’s covenantal Zionism requires that he revere them. And it requires, as well, a mourning for the glorious community that was destroyed:

Such was the city of our youth. She is no longer. We will never again return to her. Her houses stand, her gardens are green, her trees still turn in fall. Even the school where we studied still stands on the hill. But it is our city no more. Our world is destroyed; it will not rise again. We will never again go to the streets of Brisk, where there are no Jews. There is nothing for us there—only the memory of the ashes that have scattered we know not where.

This is something Begin seems to have often said: that he will never return to Brisk. Nor could he have ever imagined that one day, in a post-cold war Belarus, a bust of Menachem Begin would be established in Brest, the current name of that city. Menachem Begin, has, in a sense, returned to Brisk.

But the larger context of how Begin described the fact that would never again return to the city of his birth is important. Writing twenty years before this speech, Begin contributed to a book of essays about Brisk. There he writes:

No. No. I will not allow myself to go back to Brisk. Yet Brisk will always follow me and be with me. Because the three main things I have learnt were instilled in me in sorrow and also in joy that I have carried with me from my childhood home—with me during the nights of conflict and the days of joy. Here they are:

- Love your fellow Jews.

- Do not fear the Gentiles.

- Lucky is the man who carries the yoke of his childhood with him.

Yes, Begin will never leave Brisk, but he will gladly bear forever the yoke of his childhood home. And in this speech, more than any other, he will illustrate why this is so. In the most moving part of the eulogy, Begin recalls the High Holy days of his childhood:

But there are still days or nights, I believe, when every one of us is still in the city of our youth. I will tell some of my own experiences. It was nearly 50 years ago that we invited a cantor to the great synagogue, and for him we created a community choir, with him at its center; it was called ha-m’shor’rim, [The Singers].

In those days we had a ritual slaughterer named Prager. During my youth I would go to the middle of the city to bring him birds to slaughter for kapparot [the ritual killing of chickens, which are then fed to the poor, on the eve of Yom Kippur]. He had a son, a friend from class; Berele was his name. And he was one of ha-m’shor’rim.

Here too, we must take note of Begin’s affectionate reference to kaporos, which was not a halakhic obligation but rather a tradition of daily Jewish life. In this reference he reveals his intimacy with these traditions, and his fond participation in them. And in this acknowledgement, we see how Begin’s worldview differed even from other those who initially inspired his Zionism.

To wit: Menachem Begin revered Zev Jabotinsky, and even referred to him by the traditional Jewish term mori v’rabi, my master and teacher. And yet, Jabotinsky, in a famous letter to Ben-Gurion about how much he desired a Jewish state, once wrote with what can charitably be described as a lack of reverence for the everyday traditions of Diaspora Jews:

I can vouch for there being a type of Zionist who doesn’t care what kind of society our “state” will have; I’m that person. If I were to know that the only way to a state was via socialism, or even that this would hasten it by a generation, I’d welcome it. More than that: give me a religiously Orthodox state in which I would be forced to eat gefilte fish all day long (but only if there were no other way) and I’ll take it.

To achieve Zionism’s ultimate goals, Jabotinsky would even eat gefilte fish! (But only if there were no other way.) Begin revered Jabotinsky, and there is much about Jabotinsky to revere, but he could never have written these words.

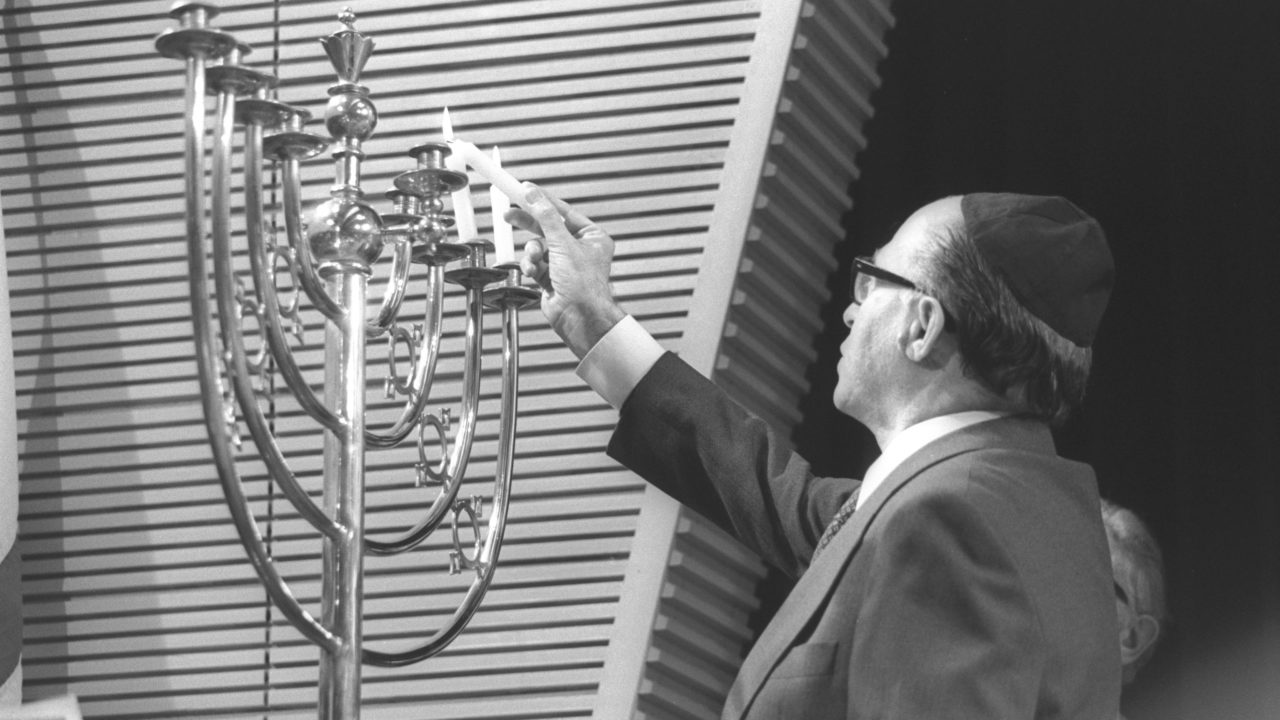

Hart Hasten, an intimate of Begin, recalls being in the prime minister’s office as seven members of the ḥaredi political parties stormed in, angry about something or other. Begin sat silently as they yelled, and then, as they paused, he placidly replied in Yiddish: raboysai, have you already davened minḥah (Gentlemen, have you already said the afternoon prayers)? Stunned, they said that no, they had not davened minḥah. Begin, with Hasten and his chief of staff, Yeḥiel Kadishai, formed a minyan with their fellow Jews, whose rage had dissipated. Begin knew how to daven, and he understood the power of davening. And it was the davening of Brisk that he would never forget:

He had a voice that would be called alt [old] in Yiddish. Indeed, we heard the voice of a nightingale. On the night of Kol Nidrei, nearly 50 years ago, he sang with his fellow singers. I still remember today the sound, what we called in the old tongue the Ya’alot of Kol Nidrei, [a liturgical poem recited near the end of the Yom Kippur evening service]. . . . And in the special holiday prayer on Rosh Hashanah, Berele would sing solo: “Is Ephraim not my dear son? A pleasant child? As I speak of him, I do earnestly remember him still: therefore my bowels are troubled for him; I will surely have mercy upon him, saith the Lord” [Jeremiah 31:20]. Until today I hear his voice in this prayer, or the prayer in his voice.

Here too, observe the difference between the lives of Menachem Begin and his father, Ze’ev, and those of other Zionist leaders. Hillel Halkin, in his excellent biography, describes how Jabotinsky, at the end of his life, asked someone to teach him Kol Nidrei, the dramatic liturgy said on the evening of Yom Kippur. Naftali Lau-Lavi similarly describes, in his own memoir, how he accompanied then-foreign minister Moshe Dayan to Orthodox Yom Kippur services in America, and had to explain to him, utilizing the pages of the prayer book, the Kol Nidrei, the most beloved liturgical experience in the Jewish world. Unlike Jabotinsky and Dayan and many other important figures from Jewish national life, Begin was never disconnected from the rhythms of the Jewish calendar, still recalling in 1972 the haunting memories that unite him with his audience, and with his fellow Briskers, both “those who are here today and those who are not here today.”

One of those who was not present as Begin gave this speech was Berele, the murdered son of the town’s ritual slaughterer, a boy with the voice of a nightingale, a voice that transports him back to the synagogue where he once prayed, uniting him with the murdered Jews who once prayed there.

In an astonishing line, Begin describes how, to this day, he hears not only the voice of the boy’s prayer, but also “the prayer of his voice.” Intentionally or not, Begin has hit on another insight first famously established by Rabbi Ḥayyim of Brisk, the rabbi whom he saw as a shutaf, a partner. True prayer, Rabbi Ḥayyim argued, is as the Talmud describes it: avodah shebalev, service of the heart. Without the inner prayer, the external words are insignificant. There is, in other words, no voice of prayer without the prayer in the voice. Prayer is service of the heart—and when that is achieved, then one can draw the congregation together in a way that they will never forget, so that the boy who once sang a solo will live still.

There is another element in this description that bears noting. In a union of medium and metaphor, Begin describes Berele’s singing the zikhronot, the passage of prayer on the High Holy Days that is about memory. Begin, in other words, is remembering how Jews remember. And the verse that Berele sang, as Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik pointed out, is one of the most extraordinary illustrations of how powerful memory in Judaism is.

God, the latter Rabbi Soloveitchik argued, speaks as a mother about Israel; even as Ephraim, the northern kingdom, is punished and exiled, God cannot forget the people as the “child” they once were. Rabbi Soloveitchik observes that for the mother, “the image of the baby, the memory of an infant held in her arms, the picture of herself playing, laughing, embracing, nursing, cleaning, and so forth, never vanishes. She always looks upon her child as upon a baby who needs her help and company, and whom she has to protect and shield.” And now, a grown man himself, Begin in turn refuses to forget the lives and longings of his own parents. In fact, as we will soon see, it is precisely those lives and longings from so long ago that kept Begin focused on building up the Jewish state.

In this speech, however,he has only just begun his description of the High Holy Days. The most important part of Yom Kippur, he learned, was not Kol Nidrei or the N’ilah service at the day’s end. Rather, it was the “avodah,” the elaborate description of the service in the Temple on the Day of Atonement:

And on the afternoon of Yom Kippur, when all were fasting and in prayer shawls, not many remained within the walls of the synagogue. But those who stayed studied intensely the avodah[the liturgical poem that describes the Yom Kippur service of the Jerusalem Temple in intricate detail]. And my father would insist that especially during the recitation of the avodah one should stay and pray, since perhaps the holiness of this prayer equaled the holiness of all the holy prayers of the rest of the year. And the voice of the cantor blended with those of the singers: “and the priests and the people standing in the courtyard, when they heard the ineffable name leave the lips of the high priest in holiness and purity, would prostrate themselves and fall on their faces and say: ‘blessed is the name of His glorious kingdom forever and forever!’”

On that day, the day of Yom Kippur, and that night, the night of Kol Nidrei, wherever you may be, you find yourself in the synagogue of Brisk. And you still hear, as Berele sang, ya’ale v’yavo, just as the nightingale sang to us, and that majestic prayer: “and the priests and the people, standing in the courtyard of the Temple.”

Berele sang those words, Begin recalled, and those together in the synagogue sang them k’ilu hi t’mol shilshom, as if the ancient Temple services happened yesterday. Herein, for Begin, is the secret of how Jerusalem never disappeared from Jewish hearts. For, after Jerusalem was destroyed, it was rebuilt, stone by stone, in the memories of the Jewish people. Reconstructed in their souls, Jews have prayed for its physical restoration ever since.

Incredibly, another child of Brisk, with a very different career, gives us a similar description. The previously mentioned Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik had perhaps been in the very same synagogue, and had seen his grandfather, Rabbi Hayyim, praying during the Avodah. He described it six decades later in a Yiddish address that can be seenon YouTube:

Both Reb Ḥayyim and my father understood the avodahthoroughly in all its detail. They recited it with such enthusiasm, such ecstasy: their entire personalities were caught up in ecstasy. They couldn’t tear themselves away—it was a beautiful reality—not the reality of Brisk, of the street. . . . It was another reality, a reality that they enjoyed so much that they couldn’t break away from it. . . . Whoever listens closely to the tune of V’hakohanim v’ha’am [“and the priests and the people . . .”] doesn’t have to hear anything else but the tune alone to feel the nostalgia and the yearning for what once was the great beauty of the avodah. . . . We talk about how beautiful the Beys Hamikdash [Temple] was. How good it was for all Jews that their prayers were accepted. . . . . When I stood next to my father and grandfather, I felt like rejoicing along with them, with the rest of Israel.

Rabbi Soloveitchik further commented, in another address, that “if the destruction of the Temple did not destroy the Jewish people,” it was due to the fact that the Temple which they built and preserved in their hearts, this emotional edifice, “the empires of Babylonia and Rome were utterly unable to conquer.”

Begin, similarly, is saying that if Jews remained existentially linked to the land of Israel, it was because they had continued to gather in locations such as the great synagogue of Brisk on that sacred day, preserving in their hearts and in their souls the image of ancient Temple services as if they happened just yesterday.

Of course, it was not only Jewish tradition, but also modern Zionism, that formed Begin. Begin learned from his Zionist father, and from Jabotinsky, to fight back against the anti-Semites, not to fear them; he needed to learn from his two mentors in Zionism that the redemption of the Jewish people lay, at least partially, in their own hands. But in “We Were All Born in Jerusalem,” just five years after the Six-Day War, Begin still insisted that the glory of the conquest of Jerusalem belonged not only to the IDF but to the generations of countless Jews who stood in synagogues like those of Brisk and brought the Temple back to life:

We will remember their love and sanctify it just as we merited to free the Land of Israel and redeem Jerusalem. “And the priests and the people, standing in the courtyard of the Temple”—this was the prayer they recited. And the day came that we redeemed Jerusalem, and we have dug into its dirt, and we have walked the path and so we have seen the Gates of Ḥuldah [that lead into the Temple]. They are still locked. And behold the mighty stones the Roman legions threw downward, covering the gates for 1,800 years. But they are there before our eyes. . . . They ascended to the Gates of Ḥuldah through the courtyard and the woman’s courtyard—and you can see it, as if it were just yesterday.

Here too, incredibly, Begin focuses not on the most well-known aspect of the Old City, the Western Wall. Rather, he discusses the “gates of Ḥuldah,” the entrances to the Temple Mount on the southern side, through which hundreds of thousands of pilgrims once streamed. He illustrates an intimacy with the makeup of the Temple, and he shows thereby how the services of Brisk kept the Temple alive in the hearts of Jews, so that they could one day return to Jerusalem.

As I reread Begin’s words, we are about to mark Jerusalem Day, the anniversary of Jerusalem’s conquest. The emotions that arise in me are reverence mixed with regret. It is hard not to think of the fact that the conquest of Jerusalem was almost immediately followed by handing the keys of the Temple Mount back to the Waqf, so that the state of Israel’s greatest miracle was followed by its most terrible mistake. I have argued elsewhere in Mosaic why I think this was such a tragedy, and what I believe the Israeli policy toward the Temple Mount ought to have been. Today, the gates of Ḥuldah remain shut, and those who hold the keys to the mount have, over the decades, sought to destroy all physical evidence that Jews once engaged there in the avodah so lovingly recollected by Begin.

Begin’s eulogy for Brisk reminds us of Israel’s unique responsibility to act to secure the safety of the Jewish people, but also to preserve the vision of those who had come before, those who had died before there was an Israel to protect them. If it fails to do so—if, for Israel, the 2,000 years of persecution is merely a reminder that Jews need protection and nothing more—than the debt to the past is unpaid.

But if their vision is allowed to live, then those who died live still as well:

Brisk. From there we came. But we were born in Jerusalem.

“And the priests and the people, standing in the courtyard of the Temple,” as if it were the day before yesterday. . . . Gratitude to our fathers, gratitude for their love of the Land of Israel, gratitude for their prayers, gratitude for their faith in the coming of the messiah. [As the traditional statement of faith has it:] “And even though he may tarry, I nevertheless await him.” Our parents did not have the opportunity, but their children after them conquered the “beginning of redemption.” And so with love of Israel, with love for the Land of Israel and for Jerusalem, we will sanctify their scattered ashes, elevate their souls in holiness and purity, and carry in our hearts the memory of their love from generation to generation.

Five years after speaking these words, Menachem Begin became Prime Minister of Israel, uniting diverse groups by his combining Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionism with a reverence for Jewish faith. And in an Israel and Jewish world that remains divided, we look again for a Jewish leader who can, in his or her own way, embrace the vision of Jabotinsky while still speaking with love and longing, and with equal eloquence, of v’hakohanim v’ha-am ha-om’dim ba-azarah, “And the priests and the people, standing in the courtyard of the Temple.” Such a figure has yet to arise.

As I wept on that day in the Inbal Hotel for the world of my forefathers that was no more, I rejoiced in the recovery of this speech, in the unique leadership of Menachem Begin, and I also felt a foreboding that we may never see his like again.

This essay was originally published in Mosaic.

What Begin’s 1972 elegy for the diaspora reveals about a worldview unique among Israel’s founders.

What Begin’s 1972 elegy for the diaspora reveals about a worldview unique among Israel’s founders.