Misunderstanding the Drops of Wine

Why do we remove drops of wine at the seder?

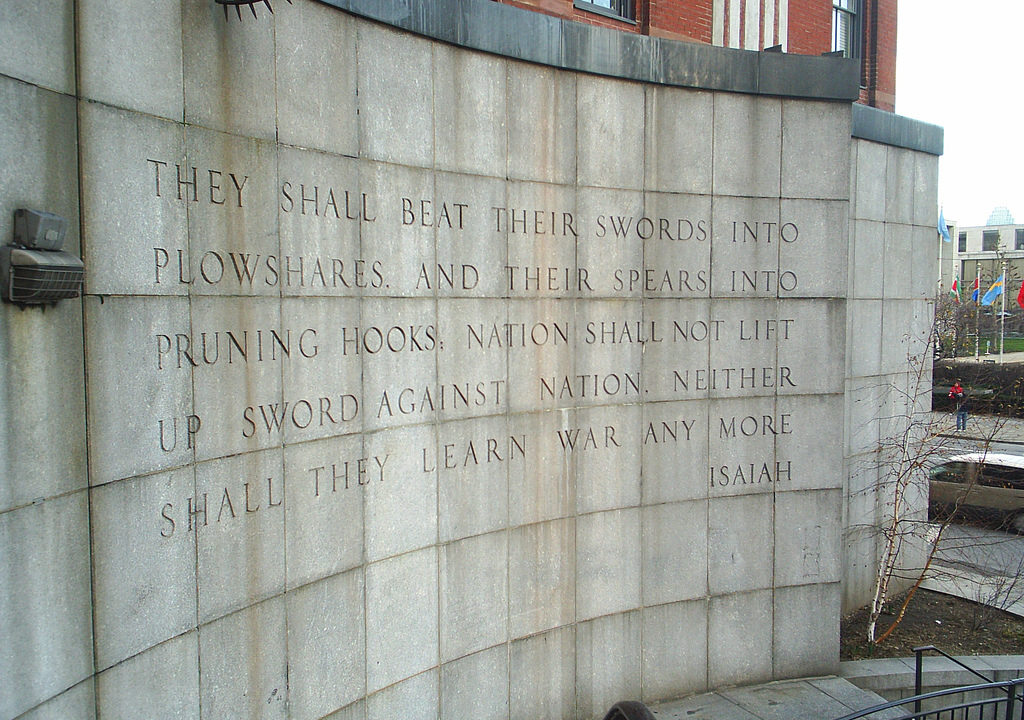

On First Avenue in New York City, across the street from the United Nations General Assembly, sits what is known as the Isaiah Wall. Inscribed on the structure, in large, ornate letters, are the words of the Hebrew prophet who gave the wall its name: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” These sentences conclude Isaiah’s prediction of the “end of days,” when all the nations of the world will recognize the God of Jacob and join Israel in serving Him in Jerusalem. The verse reflects one of the most sweeping, audacious, and universalistic beliefs in Judaism, and its presence on the Upper East Side, adorning the United Nations, cannot be seen as anything other than utterly inappropriate. For it is at the UN, more than at any other location on earth, where dictators are welcomed, tyrannical nations celebrated, and the peoples of the world gather to collectively deny the rights of the people of Israel and Israel’s historic connection to Jerusalem.

For those who recognize the incongruity of the verse’s location, the Isaiah Wall embodies an important reminder. While Judaism does indeed look forward to a time of universal peace, it also insists that this cannot come about without the defeat of evil. Jews have always looked forward to a time without war, but Jewish tradition also recognizes that at times we must give war a chance. Even as Isaiah looks forward to weaponry being rendered obsolete, the prophet Joel speaks of the exact opposite:

Proclaim ye this among the Gentiles; Prepare war, wake up the mighty men, let all the men of war draw near; let them come up: Beat your plowshares into swords and your pruning hooks into spears: let the weak say, I am strong.

Joel, as biblical scholars note, is deliberately reversing Isaiah’s words to stress that Isaiah’s vision is contingent upon his own; the wicked must be fought in order for war to cease.

This profound moral and political point lies at the heart of the structure of the Passover seder. One of the most renowned and venerable traditions of the evening, unmentioned in the Talmud but perpetuated for centuries, is the removal of a bit of wine from one’s goblet at the mention of each of the ten plagues, the divine wrath wreaked upon Egypt. Today, most Seder participants believe that this ritual illustrates that our joy is diminished at the punishment of others. It is an explanation that is famous, ubiquitous, cited by Jews devout and secular alike.

And it is utterly unfounded in Jewish tradition.

In fact, the point meant to be made by the removal of wine is the exact opposite of what is assumed. One of the earliest documentations of this ritual is that of the 14th-century German rabbi Jacob Moelin, known as Maharil, in his collection of Jewish traditions. We remove the wine, he writes, in order to express our prayer that God “save us from all these and they should fall on our enemies.” The drops, in other words, express our desire that the visitation of the Lord’s wrath upon Egypt should happen to others, to every evil empire on earth. Though we definitely do not delight in the death of innocents who may also have suffered during the plagues, nevertheless the notion that God punishes nations as well as individuals is part of biblical theology, and a desire to see wicked nations punished is bound up in the belief in a just and providential God. “The righteous shall rejoice when he seeth the vengeance,” the Psalms proclaim, and then the psalmist explains why: “So that a man shall say, Verily there is a reward for the righteous: verily he is a God that judgeth in the earth.”

As to the notion that the tradition reflects a diminishing of joy at this moment, the concept did not make its appearance in Jewish texts until half a millennium later. In an outstanding article in the journal Hakirah, Zvi Ron demonstrates that the earliest version of it was published in 19th-century Germany. It then made its way to the United States, where it “resonated with the sensibilities of English-speaking American Jews in particular, and was popularized through being presented as the only explanation for the custom in American Haggadot from the 1940s and on.” “This explanation,” Ron reflects, “came to be seen as more humane and understandable than the original explanation.”

The problem however, is that it is not more humane. We need reminders that only in the defeat of evil can innocents be saved; only when justice is done can swords finally be beaten into plowshares.

This is why the final eating of matzah at the Seder is followed by another plea for punishment: “Pour out thy wrath upon the heathen that have not known thee, and upon the kingdoms that have not called upon thy name.” This controversial sentence is also misunderstood, as it is elucidated by the verse that follows: “For they have devoured Jacob, and laid waste his dwelling place.” The reference is not to all nations, but to those who have sought to destroy the Jewish people; it, too, is a plea for the punishment of the wicked. Also missed is the significance of the paragraphs that immediately follow—psalms of praise that are largely not about Israel at all, but about a time when the “united nations” of humanity will join in praise of God. “Praise the Lord, all the nations, adore him, all the peoples,” we read in the Haggadah, followed by another stanza universalistic in nature: Nishmat kol chai tevarekh et shimkha, “the soul of every living being will bless Your Name.”

There are profoundly universalistic elements to the Haggadah. The first part of the Seder focuses on Israel and its enemies: “In every generation they rise up against us to destroy us, and God saves us from their hands.” Yet the Seder is concluded by emphasizing our shared humanity, looking forward to a time when war will cease and the words incised on the Isaiah Wall will be fulfilled. The genius of Judaism lies in its balance of the particular and the universal; indeed, its extraordinary nature consists in its insistence that only through particularism can the universal be appreciated, and only through justice can peace be achieved.

In 1981, Menachem Begin’s government annexed the Golan Heights, and the United Nations General Assembly responded with a sweeping condemnation of Israel. The Mayor of New York, Ed Koch, announced his intention to alter the Isaiah Wall, adding an inscription that would reflect the United Nations’ “hypocrisy, immorality, and cowardice.’’ Koch’s worthy goal was not achieved. Yet the unchanged, incongruous words on the wall at the UN remind us how much evil remains in the world, and why we must pray, and work, for its defeat. Only then will Isaiah’s vision of a world without weapons, and of nations united in service of God, be realized. May this eschatological event occur as soon as next year—in Jerusalem.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

Why do we remove drops of wine at the seder?…