One Brief Kaddish, Summer 2017

It's rightly becoming more and more mainstream for Jews to ascend the Temple Mount.

And the priests and the people who stood in the Temple courtyard, when they heard the great and awe-inspiring Name, emerging from the mouth of the High Priest, in sanctity and purity, would all fall on their faces, confess, and proclaim, Blessed be His Sovereign Name for all eternity.

Har Habayit Beyadeinu! The Temple Mount is in our hands!

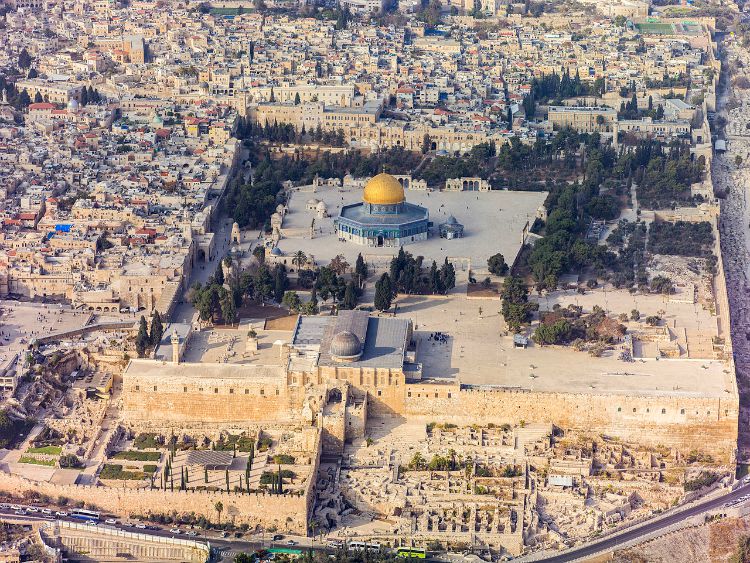

On Jerusalem Day 2017, the streets of Israel’s capital were thronging with students from religious Zionist schools, proudly parading from the new city into the old, celebrating 50 years of the sacred city’s unification. But the most interesting crowd of all assembled on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount: the more than 1,000 Jews who ascended to visit the site, more than twice as many as on any Jerusalem Day in the 50 years prior. These religious Zionists were marking the anniversary of the State of Israel’s greatest achievement—and its most tragic mistake. Whereas Israel could have acted, in the aftermath of the Six-Day War, to preserve both Muslim and Jewish rights to pray on the Mount, Moshe Dayan immediately returned the Mount—the locus of Jewish aspirations—to the Jordanian religious organization called the Waqf. The Waqf enforced a ban on Jewish prayer at the site, and engaged in wanton destruction of any evidence of the Temple that had once been there. Religious Zionists must therefore grapple with the fact that today, the only religious group without the freedom to pray at its most sacred site in the Jewish state are the Jews. Even more stunning is the fact that even as Jerusalem has been rebuilt, as the prophets predicted, the destruction of the Temple remnants has continued apace.

This paradoxical state of affairs was reified this summer. Following the murder of two police officers on the Mount, Israel’s government first installed metal detectors and then found itself forced to remove them. In the midst of this sorrowful summer, perhaps motivated by the realization that the Jewish connection to the site must be reasserted, 1,300 Jews ascended the Mount on the Ninth of Av, when the Temple’s destruction is mourned.

The masses of Jews on both Jerusalem’s most joyous day and its most sorrowful one revealed a trend: The Temple Mount is fast becoming a pilgrimage site for religious Jews. In the past, most abstained from visiting out of concern that they might enter a sacred area in a state of ritual impurity, but many now believe that, with a knowledge of the layout, history, and religious laws pertaining to the location, it is permissible to visit certain parts of the Temple Mount Plaza. They thus visit the site under religious guidance, immersing first in a ritual bath, or mikveh, and tread only in specific areas. What was once a trickle of pilgrims has become a stream, and this year, they numbered in the many thousands.

Meanwhile, Jewish media “experts,” in the face of this expanded Jewish pilgrimage, discuss the subject with an astonishing lack of knowledge about the subject. One example is a recent article in the Atlantic by Jeffrey Goldberg, in which he describes these Jews as a “small group of radical religious innovators,” linking to an article that he wrote on the subject in 1999. A simple Google search would have revealed the sea change that has taken place in the past 15 years, and how the truth is the exact opposite: The segment of Jews visiting the Temple Mount is becoming more and more mainstream, supported by rabbis noted for their liberalism in social or religious affairs. One prime example is Rabbi Yaakov Meidan, a leader of the Har Etzion Yeshiva and co-author of the Gavison-Meidan covenant, a proposed constitution for Israel composed with the secular legal scholar Ruth Gavison. A movement that was once “limited to extremist politicians,” in the words of the Times of Israel’s Amanda Borschel-Dan, “has today garnered support from a who’s who of religious leaders.”

Journalists combine their misinformation about the social situation with an ignorance of what the Temple means to Jewish tradition. “The Holy of Holies,” Goldberg writes, “is the room in which the Jewish high priest spoke the Tetragrammaton, the ineffable name of God, on Yom Kippur.” No. The High Priest spoke nary a word in the Holy of Holies. He pronounced God’s ineffable name in the Temple’s courtyard, in the presence of the people, as they fell on their face in devotion to the Temple and the God Who dwelled therein. For centuries, a remembrance of this moment was a high point of the Yom Kippur service in every synagogue on earth, keeping the Temple alive in the Jewish soul. In a tribute to Lithuanian Jews murdered by the Nazis in 1942, Menachem Begin recalled being taken by his Zionist father to the synagogue on Yom Kippur for the avodah, the prayer that describes, in exquisite detail, the High Priest’s Temple service.

And the priests and the people who stood in the Temple courtyard—[remembering] as if it were yesterday. This is in our spirit, our gratitude to our fathers, gratitude for their love of Eretz Israel, gratitude for their prayers . . . and thus, with love of Israel, love of the Land and of Jerusalem, we shall sanctify their scattered ashes, raise their souls with holiness and purity, and carry in our hearts the memory of their love from generation to generation.

In the midst of the metal-detector contretemps, the Waqf declared that it would boycott the Temple Mount. Visiting Jews were, for a brief and brilliant moment, able to utter several words of prayer without interference. The Israeli media published photos of a diverse group of Jews standing on the Temple Mount reciting the Kaddish, so close to where their ancestors, on Yom Kippur, had once stood listening to the High Priest pronounce the Name of God. Soon after this Kaddish, the Waqf returned; Jews again were no longer free to pray at the site toward which all Jewish prayer has been directed for thousands of years. But images of that one unimpeded Kaddish remain; to study them is to look back on the miraculous and heartbreaking past half-century in Jerusalem, to celebrate what has been achieved, and to mourn what might have been.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

It's rightly becoming more and more mainstream for Jews to ascend the Temple Mount.

It's rightly becoming more and more mainstream for Jews to ascend the Temple Mount.