‘Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land’

Rediscovering the biblical story of the Liberty Bell and what it reveals about the Hebraic grammar of American freedom.

On July 4, 1976, in honor of the bicentennial and during Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Philadelphia, the government of Great Britain decided to present a special gift to the American people. What has become known as the “Liberty Bell” had originally been commissioned by Pennsylvania from the Whitechapel bell foundry in London; but when the bell arrived in America, it immediately cracked and had to be recast by the American craftsmen Pass and Stowe. The British therefore decided to have the Whitechapel foundry create a new bell in honor of the 200th anniversary of American independence, making up for the lemon that had originally been sent. This further allowed a visiting Elizabeth, a descendant of George III, to show that there were no hard feelings.

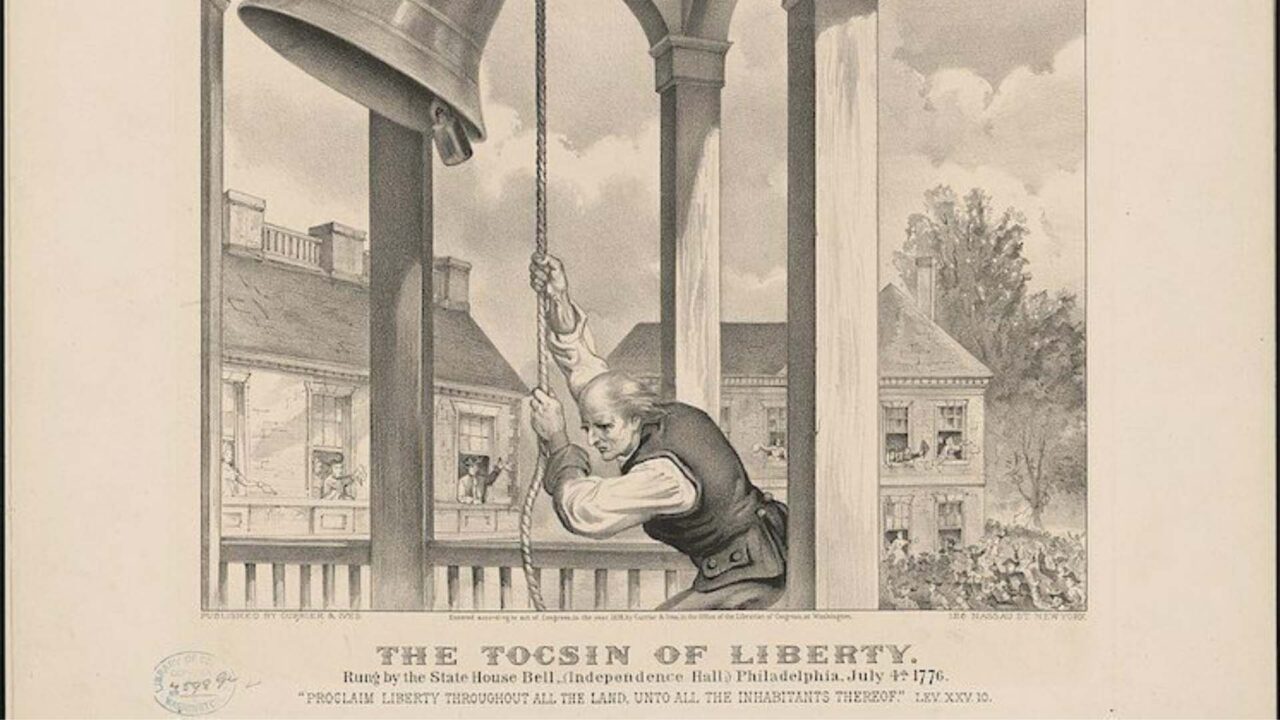

It was a lovely gesture, highlighting how profoundly the bell has become associated with the Fourth of July. This association stems from a tale published in the 1840s by George Lippard, which portrayed an elderly man in 1776 who had been charged with ringing the State House Bell when independence was announced—with the man waiting, waiting, for a young boy to bring him the news of the Continental Congress’s declaration on the Fourth of July. Unfortunately, the entire tale was fiction, a fabrication of the author. While the bell would have been rung to celebrate American independence, it would have been one of many sounded in the city, and only on July 8, several days after Congress’s fateful decision. The true tale of the bell—and the family that brought it into being—is interesting enough; and it is indeed bound up with the unique story of American freedom, containing a profound lesson for our time.

The story begins in 1701, when William Penn enshrined in Pennsylvania a Charter of Liberties guaranteeing freedom of conscience. For Penn, a Quaker, true friendship with God and man could not be coerced: “There can be no friendship where there is no freedom.” Penn’s agent in the region was James Logan, later mayor of Pennsylvania. The historian Edwin Wolf describes how Logan “bought himself Hebrew Bibles and Hebrew prayer-books, and read them and made notes in them. When he was more fluent, he added a Shulhan Arukh and the great six-volume edition of the Mishna with the Maimonides and Bertinoro commentaries. In fact, Logan gathered together in Philadelphia in the first half of the eighteenth century one of the largest collections of Hebraica which existed in frontier America.”

Logan, Wolf explains, then taught Hebrew to his daughter Sally, whom he described as a child “reading the 34th Psalm in Hebrew, the letters of which she learned very perfectly in less than 2 hour’s time, an experiment I made of her capacity only for my Diversion.” Sally, in turn, married Isaac Norris, speaker of the State Assembly. Norris was a Hebraist in his own right, though his father-in-law, amusingly, seemed unimpressed, saying of the man who married his gifted daughter, “If he had as much skill in ye Greek as he has in Hebrew he would merit the general reputation of a Learned man.”

It was from this Hebraic household that the bell emerged. In 1751, Isaac Norris commissioned it from Whitechapel to mark the 50th anniversary of the Charter of Liberties. He chose to emblazon the bell with words from Leviticus, describing how every 50 years, indentured servants are freed: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof….It is a jubilee, and each man shall return to his heritage, each man to his family.”

As Gary B. Nash notes in his history of the Liberty Bell, the chosen verse reflected a deep knowledge of the Hebrew text; and it was after America’s second great awakening that others truly came to appreciate its biblical context as well. Known until the 1830s as the “State House Bell,” anti-slavery advocates chose the bell because of its verse, renaming it the “Liberty Bell” as a symbol of the abolitionist cause.

“May not the emancipationists in Philadelphia,” one abolitionist paper reflected, “hope to live to hear the same bell rung, when liberty shall in fact be proclaimed to all the inhabitants of this favored land? Hitherto, the bell has not obeyed the inscription; and its peals have been a mockery, while one sixth of ‘all inhabitants’ are in abject slavery.”

Thus the bell and the verse upon it embody how biblical imagery inspired the assault on slavery and the advancement of the American idea. By the 1840s the bell had cracked and gone mute, but it was still used, a century later, to illustrate, as Abraham Lincoln once reflected, that America stood for more than independence, “something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come.” On D-Day, in 1944, Philadelphia mayor Bernard Samuel struck the bell with a mallet, and the tones broadcast around the world. Speaking at Pointe du Hoc in 1984, Ronald Reagan reflected what that meant to those who landed in France:

The Americans who fought here that morning knew word of the invasion was spreading through the darkness back home. They fought—or felt in their hearts, though they couldn’t know in fact, that in Georgia they were filling the churches at 4 A.M., in Kansas they were kneeling on their porches and praying, and in Philadelphia they were ringing the Liberty Bell.

Something else helped the men of D-day: their rock-hard belief that Providence would have a great hand in the events that would unfold here; that God was an ally in this great cause.…That night, General Matthew Ridgeway on his cot, listening in the darkness for the promise God made to Joshua: “I will not fail thee nor forsake thee.” These are the things that impelled them; these are the things that shaped the unity of the Allies.

Strikingly, the bell recast by Whitechapel in 1976, boldly emblazoned by Britain with the words “let freedom ring,” lacked the Levitical verse, the extraordinary link between the American conception of liberty and the heritage of the Jewish people. It is therefore all the more striking that when July 4, 1976, actually dawned in America, something unexpected occurred in Jewish history that truly embodied the Liberty Bell.

On that July 4, Americans woke up expecting the headlines to be about the bicentennial of America, and discovered that after midnight, Israel had engaged in a miraculous mission to rescue over 100 hostages in Entebbe, Uganda. Speaking at the United Nations, Israeli ambassador Chaim Herzog argued that this had been a victory for the entire free world: “We are proud not only because we have saved the lives of over 100 innocent people—men, women, and children—but because of the significance of our act for the cause of human freedom.” The Israelis had, on the American bicentennial, proclaimed liberty throughout the land and fulfilled, for the hostages, the very same biblical verse: “Each man shall return to his heritage, each man to his family.”

The Bell’s biblical story is worth rediscovering today. We are experiencing what Commentary has called “the great unraveling,” in which many on the left assail the greatness of America, describing its story as a series of unmitigated sins. Meanwhile, even on some segments of the right today, we hear dismissal of the universality of the American idea, and of a foreign policy that seeks to support liberty around the world. The bell embodies a people who, ever imperfect, ever exceptional, were inspired by the Bible to advance the cause of liberty on its own soil and throughout the world.

In 2004, on the 60th anniversary of D-Day, the people of Normandy dedicated a near-exact replica of the bell and rung it over the cliffs of Normandy, with the original sound of the bell echoing over the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc. We cannot fail to see in this a reminder of our obligation to preserve the true tone of the bell, the Hebraic grammar of American liberty, until more Americans are willing to hear it again.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

Rediscovering the biblical story of the Liberty Bell.

Rediscovering the biblical story of the Liberty Bell.