Rembrandt’s Very Human, Very Accurate, Very Jewish (and Very Unclassical) David

Michelangelo’s universally admired depiction of one of history’s most famous Jews is not the least bit Jewish. Take, on the other hand, Rembrandt.

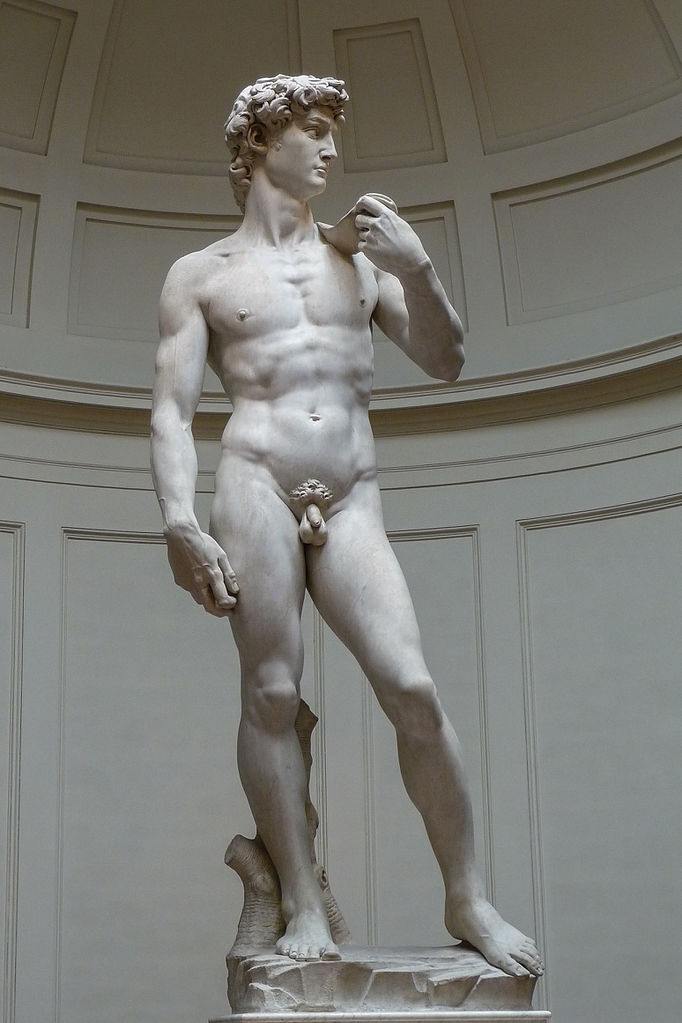

Perhaps the most famous sculpture in the world is Michelangelo’s heroic statue of the biblical David (1504). Standing over fourteen feet tall in the Galleria dell’Accademia in the center of Florence, it is surrounded perpetually by hordes of enraptured art lovers and tourists. The nude, Adonis-like youth stands before them, muscled, vigilant, poised, calmly holding a sling over his left shoulder while loosely clenched in his right hand rests the deadly stone that in an instant will be launched at the giant Goliath.

It is a very great masterpiece. Yet this universally admired depiction of one of history’s most famous Jews is not the least bit Jewish.

Michelangelo’s ambition, as Simon Schama has written, “was to approximate men to gods.” Inspired primarily by antiquity, as were other Renaissance artists, he translated mortal humanity into something purer, chillier, more enduring, and in his sculptures undertook (again in Schama’s words) to “tease out from the marble those ideal forms he believed lay trapped within it.” And so it is with his David, whose “heroic power . . . lies precisely in [the statue’s] inhumanly frozen immobility.”

How different is the small etching of King David executed by the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn in 1652. Rather than fourteen feet tall, it is a mere six inches high. Rather than a heroic face and chiseled abdomen, we see only a vaguely etched form. Rather than being poised to strike in battle, Rembrandt’s aged David is on his knees, his elbows resting on a bed, in passionate prayer. Neither arrogant nor confident, he is humble and broken. Far from embodying the very essence of regal manhood, the great king of Israel is all too unreservedly human.

And this tells us something profound not only about David himself but also about Rembrandt and the genius of his art. As a young painter, Schama reflects,

Rembrandt always resisted. . . recommendations that he visit Italy if he truly wished to realize his potential. Not that he was incurious about the Italian masters. But if one can hardly imagine Rembrandt assiduously sketching and copying the antiquities of the Capitoline, it is because he was both aesthetically and philosophically disengaged from classicism.

Classicism in art, Schama continues,

aimed at pushing the real toward the ideal, the material toward the ineffable. By contrast, for Rembrandt as for other 17th-century Dutch painters, the aim was to capture not the majesty of the gods but the nature of living, breathing humanity in all of its simultaneous magnificence and lowliness.

And that is precisely what enabled Rembrandt to capture in this tiny etching the essence of David in a way that Michelangelo never could.

Rembrandt did not title his art, and the man in this etching bears no nametag, wears no crown—so how do we know he is King David? The giveaway is lying to his left on the floor: only one biblical figure was known to own a harp. And then, on the other side of the king, there is a second telltale object: a book that clearly represents sacred scripture. David is thus kneeling between the two emblems most associated with his own sacred history: the harp and the book, and in his case especially the book of Psalms, so many of whose sublime poems are attributed directly to him.

But here the harp is strewn on the floor, and the book lies unopened. David is praying, but without benefit either of his musical instrument or of the word of God. At this moment, neither one can help him. His infant son is dying, and the usual modes of spiritual expression are of no avail. All he can do is pour out his pleading heart to God.

And this helps answer another question: why the bed? The Bible tells us only that David lies on the floor praying to God for seven days. But Rembrandt has deliberately placed him, Schama notes, before “the altar of his transgression.” For David here is pleading for the life of the child borne to him by Bathsheba, with whom he has committed adultery and whose husband he himself ordered to be killed. The bed, framed by a curtain gathered and folded over the bedposts, recapitulates his sin. Indeed, I would add that Rembrandt may well be taking his inspiration directly from the torrent of words David poured out before God after being scathingly chastised, for that very sin, by the prophet Nathan:

A Psalm of David when Nathan the prophet went to him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba.

Have mercy upon me, O God,

According to Your lovingkindness;

According to the multitude of Your tender mercies,

Blot out my transgressions.

Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

And cleanse me from my sin.

For I acknowledge my transgressions,

And my sin is always before me. . . .

In a visit to Rembrandt’s home a few years ago, I noticed a bed that looked exactly like the bed in this etching of David. It was a Dutch bed, the sort of bed where, in Rembrandt’s age, and in every home, life was conceived, life was begun, and life was ended. No one could have been more sensitive to this than Rembrandt, who had stillborn children from his beloved Saskia and one son who survived. But just as that bed represents the fragility of life, the mortality inherent in life, it also represents the potential of future life. Although David does not yet know it, Rembrandt knows, and we know, that although God does not heed his prayer before this bed, and his infant son will die, soon another son, Solomon, will be conceived in it, and through that conception the Davidic line will be preserved.

As the historian Thomas Cahill has written, we have two sources for the life of David. The outer story is told in the book of Samuel, “an early Israelite history. But David’s inner story, the story of his emotions, is told in another book, the book of Psalms”—a book utterly unlike anything else known in classical and ancient literature.

David composes rhapsodies of jubilation to God when he defeats his enemies and poems of fear and petition when he is fleeing from them, hymns of gratitude when he is studying God’s law and laments of remorse and penitence when he has desecrated it, paeans of praise when his kingship is secure and pleas for succor when it is tottering. For David, there is no part of his life, no part of his achievements and failures—political, familial, or social—and no part of his quintessentially flawed yet quintessentially devout human heart that is not opened up in poetry to the world, and to generations of Jews after him.

Therein lies Rembrandt’s deep interest in David, and in this scene in particular.

During any given year in Florence, Michelangelo’s David is visited by a million tourists. How many more have seen it in the half-millennium since it was completed in 1504, and have had their image of David formed in their minds by what they see with their eyes?

But here consider a final contrast. According to the Bible, when the prophet Samuel first arrived in Bethlehem to anoint the next king of Israel after Saul, he sought out someone tall and strong, someone like Saul himself, who stood “head and shoulders above the people”—someone, we might say, who looked like Michelangelo’s David.

God, however, sternly instructs Samuel that his entire aesthetic approach is fundamentally flawed:

Look not on his countenance, or on the height of his stature; because I have rejected him: for the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.

What matters is not height, but heart, or character; what matters is what cannot be seen. To the eye, as the Israeli scholar Ido Hevroni points out, the young shepherd boy David, immature and slight of stature, “looks like neither king nor warrior.” But he “turns out to be both,” and much more: capable of single-handedly slaying a giant on the battlefield, of commanding the armies of God in battles still to come, of presiding over the consolidation of a kingdom, all the while maintaining the utmost faith and trust in the God of Israel to whom he will pour out his heart in joy as in contrition, in thanksgiving as in unbearable grief.

One of the last scenes of David in the Bible gives us the dying king choosing his own successor. His eldest living son, Adoniyah, has proclaimed himself king. The text informs us that Adoniyah, too, is virile and strong. Yet David has promised that Bathsheba’s son Solomon, still but a child, will reign after him. The choice facing David is like the choice that faced Samuel in Bethlehem: between, effectively, height and heart. And once again, as in Bethlehem, “the Lord looketh upon the heart.”

Which is the true David? The central message of the David story, Hevroni concludes, is that “things are not always as they are seen, or as others wish us to see them.” Because of Michelangelo, David is remembered in art almost exclusively for his idealized youthful visage and stature. But if you truly want to know who David was, it is not the pagan David who stands in Florence. It is the David in Rembrandt’s etching of that grief-stricken bedside scene. There, as Jews say to this day, David king of Israel lives forever.

This essay was originally published in Mosaic.

Michelangelo vs. Rembrandt on King David.