The Land Waited for the Jews

What Nahmanides understood about the land of Israel in 1267 that Mark Twain, in 1867, never could.

One hundred and fifty years ago, a journalist by the name of Samuel Clemens published Innocents Abroad, the book that made his career and which remained the best-selling book in his lifetime. This was not a tale of a young boy sailing the Mississippi, but of the author himself sailing the Mediterranean to pay a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For Twain aficionados, the 150th anniversary of Innocents Abroad is a literary milestone. Yet there is an aspect of the book that perhaps only religious Jews can understand—because they can take it in tandem with the reflections of a medieval Sephardic sage who took a similar journey seven centuries earlier.

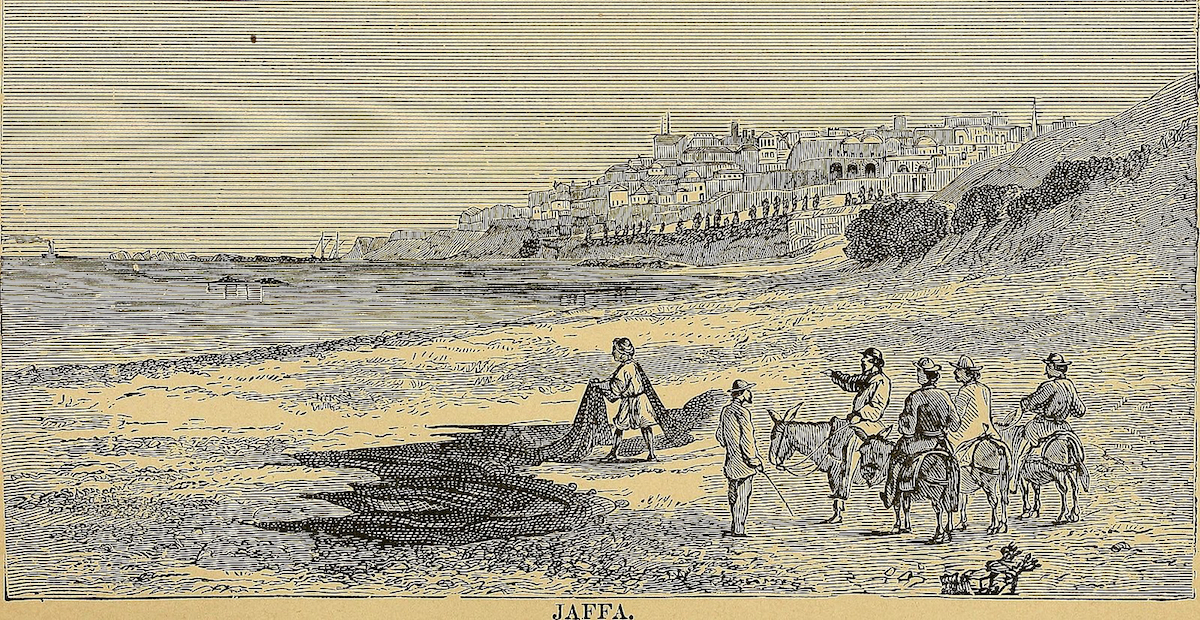

It was in 1867 that Clemens convinced a California newspaper to fund his trip on the Quaker City, a luxury cruise aboard a steamship bearing American Christians. Twain skewers much of what he sees. He pokes fun at the pilgrims with whom he was travelling. They had “dreamed all their lives of some day skimming over the sacred waters of Galilee and listening to its hallowed story in the whisperings of its waves, and had journeyed countless leagues to do it.” But they then insist on bartering with the Arab boatman because they thought the fare was too high. He mocks, as well, many of the traditional religious sites, including a spot in the Holy Sephulcre known as the burial place of Adam, the first man.

Yet the centerpiece of his biting wit is the anti-climactic nature of the place itself. The land supposedly flowing with milk and honey was anything but. In the Galilee, Twain saw here and there some “evidence of cultivation,” at most “an acre or two of rich soil studded with last season’s dead corn-stalks.” Yet the closer they came to Jerusalem, “the more rocky and bare, repulsive and dreary the landscape became.” No sight is more “tiresome to the eye,” he reflected, “than that which bounds the approaches to Jerusalem.” Palestine, he concluded, “sits in sackcloth and ashes,” and he cites the suggestion that the Israelites could have seen it as a goodly land only because of their “weary march through the desert.”

As Rabbi Moshe Taragin and others have noted, the author of Innocents Abroad had a distinguished predecessor. Exactly 700 years before, one of the most important rabbis in Jewish history arrived in the Holy Land. He saw exactly what Twain saw but interpreted it very differently. Moses ben Nahman—known as Nahmanides or Ramban—was the leader of the Jewish community in Gerona. He was forced by the king of Aragon to defend Judaism publicly against the attacks of a Jewish apostate. After he did so, he was eventually convicted of attacks on Christianity and sent into exile. In 1267, he arrived in a Jerusalem devoid of Jews.

Nahmanides describes the barrenness of the land of Israel as ordained by God with the destruction of the Temple and the exile of the Jews by the Romans. It is for this tragedy that Jews mourn on the ninth of the month of Av, or “Tisha B’Av.” Yet Nahmanides insists that in the midst of our mourning we mark a miracle. “From the moment we left” into exile, he writes, the abundance of the land has failed to show itself. Throughout the generations, “all seek to settle it,” yet the land resists cultivation. It mourns just as its people mourn. He too notes what Twain had sensed as a paradox: that the earth grows more barren as one approaches Jerusalem. “The general principle,” he wrote to his son, is that “the holier the land is, the more desolate it remains.” After all, the Holy Land yearns for the Jews; the holier a speck of soil may be, the more it refuses to provide its fruits until the Jews return.

This year, on the ninth of Av, I studied Innocents Abroad and Nahmanides’s writings with my congregation and then boarded a plane for Israel. I type these very words while in a hotel that’s a short walk away from the Damascus Gate where Twain first entered Jerusalem. My approach to the very same city was studded with greenery, and, in reversal of Twain’s own experience, the view grew more magnificent as we approached. Isaiah’s prediction, read in synagogues every year in the weeks following the ninth of Av, has come true in our time: “For God has consoled Zion, consoled all its ruins; and he has made its desert into an Eden, and its wilderness into a garden of God.”

Nahmanides saw in 1267 what Twain in 1867 had failed to see. Clemens could never have imagined that exactly 100 years after he visited the Temple Mount in 1867, Jewish soldiers would stand there to claim it as their capital of a flourishing land. Yet credit for this wondrous event can in some sense be linked to Moses ben Nahman, whose own arrival in Jerusalem exactly 700 years before the Six-Day War marked the beginning of a seven-century Jewish presence in the sacred city. To this day, there is a synagogue in Jerusalem founded by this exiled rabbi—a man who believed that if Jews would return to Jerusalem, Jerusalem would one day return to the Jews.

Yet Nahmanides, who had been driven into exile by the anti-Semitism suffusing Christian Europe, would himself be amazed by a fascinating phenomenon he could never have imagined, but that Twain’s work predicted in its own way. Today, millions of American Christians ardently love the land of Israel and its Jewish inhabitants. Over 80 percent of evangelicals in America, according to a Pew poll, affirm that God gave the land of Israel to the Jewish people. Only 40 percent of American Jews agree. Twain may have mocked his companions, but their love of the land of Israel was genuine, and it reflects a strain of American biblical culture that remains manifest today.

This love is, in its own way, as miraculous as the blossoming of Israel itself. Just this August, as Jews mourned on the ninth of Av, the Christian Broadcasting Network sent out an email explaining that “Tish’a B’av commemorates the destruction of both the First Temple and Second Temple in Jerusalem,” as well as “other tragedies” such as “the Crusades, pogroms, the Inquisition, the Holocaust, terrorist attacks, and all forms of anti-Semitism.” The CBN asked its viewers on “this special fast” to “pray for God’s chosen people.”

The email is astounding, and it may in its own way be a harbinger of the fulfillment of another prophecy by Isaiah: that one day multitudes of non-Jews would come to praise the God of Israel in Jerusalem.

Twain and Nahmanides are an unlikely pair, yet their common reflections on their own travels remind us that history is full of surprises—and that somehow its greatest twists and turns involve the Jews. More than 30 years after publishing Innocents Abroad, the man who emerged from relative obscurity to publish the tale of his tour and become the most famous author in America, penned the essay “Concerning the Jews.” In it he reflected on Israel’s endurance: “All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

Innocents Abroad, a book that approaches the religion of the American masses with cynicism, remains, in its own way and on its 150th birthday, one of the greatest literary testaments to the reality of miracles.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

What Nahmanides understood about Israel that Mark Twain never did.

What Nahmanides understood about Israel that Mark Twain never did.