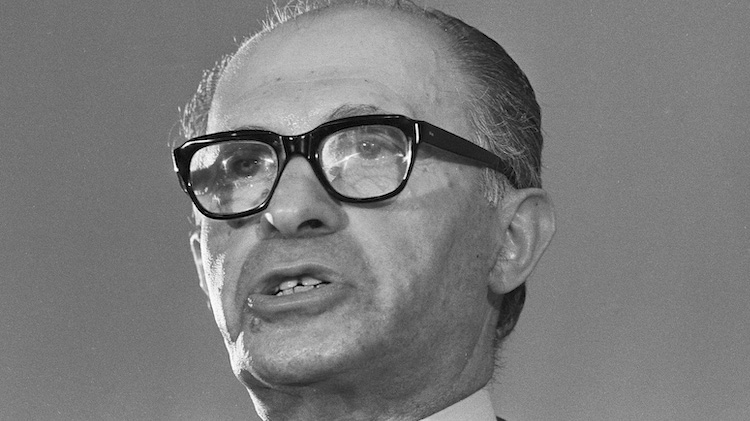

The Prime Minister and the Minyan

Among Israel's founders, only Begin sensed the key role that tradition would play in the future Israeli society.

If there was a moment that captured what became known as the mahapach—the political upheaval that marked the rise of the longtime back bencher Menachem Begin to the prime ministership of Israel in 1977—it was a private one in Begin’s office, one witnessed by Begin’s friend Hart Hasten. Following an election in which he had emerged victorious, Begin was engaged in assembling a governing coalition when the members of a Haredi party burst into his office, upset over a matter pertaining to the political horse-trading. Begin sat silently as they expressed their agitation, and then he calmly responded in Yiddish: Rabbosai, hobn ihr shoin gedavent minha (Gentlemen, have you already prayed the afternoon service)? Stunned by the unexpected query, the Orthodox men paused and then replied that they had, in fact, not yet engaged in this obligatory ritual. So, at Begin’s urging, a minyan, or prayer quorum of 10, was formed in his own office, featuring Begin, Hasten, the Orthodox Knesset members, and Begin’s chief of staff, Yehiel Kadishai. By the time the service had concluded, tempers had subsided, and, bound by a shared reverence for a millennia-old faith, Begin and his future coalition members resumed negotiations with equanimity.

It’s worth keeping this story in mind as we analyze the recent elections in Israel and the decades-long trends that have produced the country’s 37th government. Every aspect of the scene in Begin’s office would have come as a profound shock to David Ben-Gurion, the man who man oversaw Israel’s birth. For Ben-Gurion, Begin was a figure whose right-wing minority party deserved no recognition; the worldview that Begin had imbibed from his mentor Ze’ev Jabotinsky represented, in Ben-Gurion’s estimation, an element of Zionism’s past, not its future. And despite the fact that Begin was the leader of the opposition, Ben-Gurion never called him by his name, referring to him instead only as “the man sitting next to Member of Knesset Bader.” Ben-Gurion even refused to facilitate the moving of Jabotinsky’s body to Israel for reburial (the great Revisionist leader had died in New York in 1940). Begin was forced to wait until 1964 and the premiership of Levi Eshkol to secure Jabotinsky’s reinterment in the Holy Land.

Ben-Gurion would certainly be surprised, to say the least, to learn that in 2022, Jabotinsky’s movement would make Likud, the party of Jabotinsky’s heir, the largest party in Israel—while Labor, the heir to his own socialist party, would only barely make it into the Knesset.

The same surprise would have been experienced by Ben-Gurion at the role religion would play in Israeli politics and society. While prayer came naturally for Begin, Ben-Gurion would not have asked to join a minyan for minha; prayer, he reflected once in a letter now in Israel’s Library Archives, “may feel pleasant—yet it is not reality, but self-deception.” Ben-Gurion seems to have assumed that with the creation of a polity for Jews, the traditions maintained through the generations of the Diaspora would fade.

The minyan organized by Begin highlighted how he had overthrown the grip of Ben-Gurion’s political successors on Israeli public life: by emphasizing his support for the Jewish character of Israel’s civic character, by refusing to jettison public reverence for the faith of centuries, and by forging a coalition between Orthodox political parties and a base of traditionally minded Sephardic Jews who had long been taken for granted by the secular Ashkenazi elites.

It further bears mentioning that Begin did not inherit this comfort with religion from his mentor. Unlike Begin, who grew up in the famous Jewish community known as Brisk (now Brest, in Belarus), Jabotinsky was raised in cosmopolitan Odessa. Prayer was as foreign to the father of right-wing “revisionist” Zionism as it was to the socialist Ben-Gurion, or perhaps even more so; while Ben-Gurion had, in his youth, experienced traditional Jewish rituals, it was only just before his death at the age of 59 that Jabotinsky first learned the Kol Nidre, perhaps the most famous piece of Jewish liturgy. In a rare exchange with Ben-Gurion, Jabotinsky described his desire for a Jewish state, in a letter that lacked any reverence for traditional Jewish customs:

I can vouch for there being a type of Zionist who doesn’t care what kind of society our “state” will have; I’m that person. If I were to know that the only way to a state was via socialism, or even that this would hasten it by a generation, I’d welcome it. More than that: Give me a religiously Orthodox state in which I would be forced to eat gefilte fish all day long (but only if there were no other way) and I’ll take it.

While Jabotinsky’s own appreciation of civic religion may have grown over time, there was no guarantee that the nascent Israeli right in 1948 would have been sympathetic to the Jewish state being a place that cherished traditional Jewish faith. It was Begin who, as prime minister three decades after the founding, first demanded kosher food when making state visits abroad; and it was Begin who, as prime minister, first insisted that Israel’s airline not fly on the Sabbath. He argued, as Yehuda Avner recounts in The Prime Ministers, that “one need not be pious to accept the cherished principle of Shabbat. One merely needs to be a proud Jew.” It was Begin, in other words, who understood the role religious tradition would play in the Israeli future.

This understanding has been vindicated. Much has been written on the various and very different views of the members of Israel’s newest government. But less focus has been given to the remarkable fact that this seems to be the first Israeli coalition with a majority made up of Orthodox Jews. This includes not only the members of the religious parties themselves but also those MKs from the Likud who are part of the Orthodox community. And this is an accurate representation of what the country has become. As Maayan Hoffman noted in an article titled “Why the Israeli Election Results Should Not Be Surprising,” the makeup of the future Knesset reflects plain sociology: “Around 80% of Israel’s population is either traditional, Religious Zionist or ultra-Orthodox, according to official reports.”

Begin was a singular figure in Israel’s history—one who seamlessly joined deep familiarity with, and knowledge of, Jewish tradition, a personal, natural faith in the God of Israel, and a Zionism that defended both Western democratic traditions and the Jewish right to the Land of Israel. But there is no question that Israeli society today reflects the fact that only Begin among the nation’s founders sensed what the future of Israel would be.

No one, under the new government, will be forced to eat gefilte fish. But all future successful political leaders will have to understand and address the central role that traditionally religious Israelis are now playing in the country’s polity. In the ministerial offices of Israel’s 37th government—and its 47th, and its 57th—there will be many more minha minyanim yet to come.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

Among Israel's founders, only Begin sensed the key role that tradition would play in the future Israeli society.

Among Israel's founders, only Begin sensed the key role that tradition would play in the future Israeli society.