The Zionist Uncle Who Changed the World

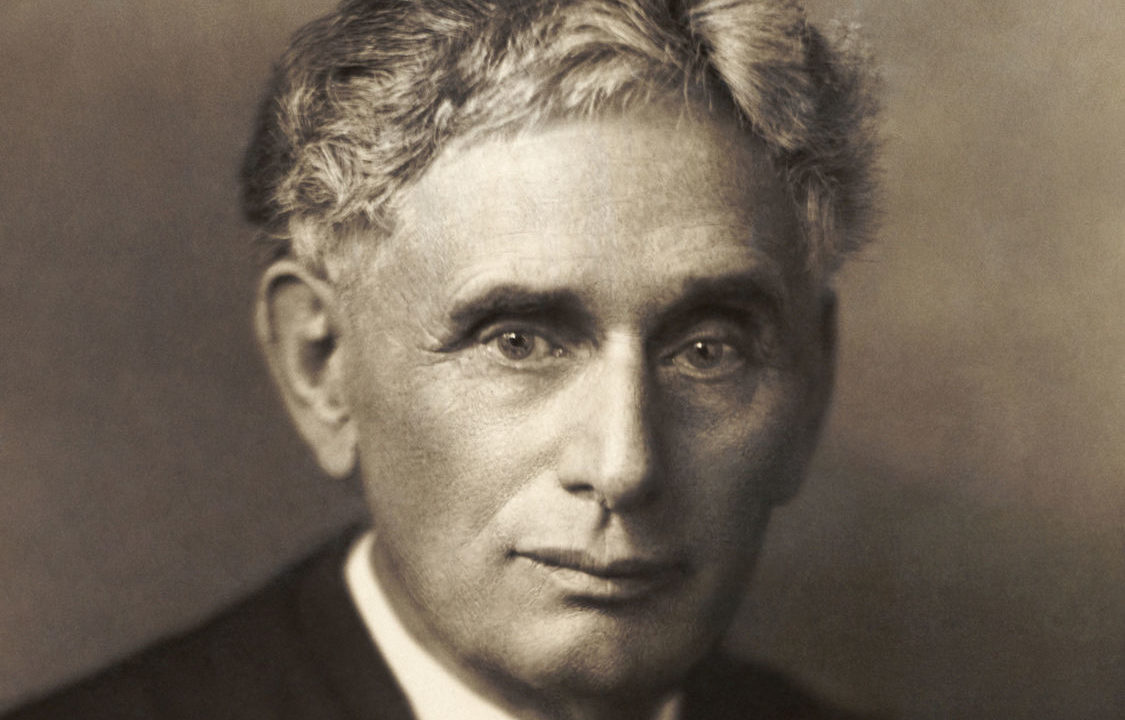

Lewis Dembitz, the uncle of Justice Louis Brandeis, had an indelible effect on his nephew's Zionism.

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.

—Arthur Balfour, November 2, 1917

As Jews in England and around the world prepare to mark the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, let us pause to ponder the respective legacies of Edwin Montagu and Lewis Dembitz. The names of these two Jews are largely unknown today, but they were, each in his own way, central players in the saga of the declaration, and therefore in one of the seminal moments in Jewish history. The former, a dedicated anti-Zionist, did everything he could to prevent this moment from occurring; the latter made his home thousands of miles from Britain and went to his grave surely unaware that the honorable way he lived his life, every day, would one day help bring the Balfour Declaration, and thereby the Jewish State, into existence.

Edwin Montagu was born into the one of the wealthiest Jewish families in England. He was the son of Samuel Montagu, who had been raised to British peerage but was known first and foremost for his zealous observance of Jewish law and for his sympathies to Zionism. Edwin’s life was lived in rebellion against his patrimony; like many members of the Jewish aristocracy known as “The Cousinhood,” he hated Zionism and its notion that Jews all around the world were one people and bound to one another. This, he believed, was not only false, but also raised the specter of dual loyalty for Jews seeking assimilation and aristocratic elevation in Britain. To Britain’s prime minister, David Lloyd George, Montagu complained, “All my life I have been trying to get out of the ghetto; you want to force me back there.”

In 1917, Montagu received the India portfolio in George’s cabinet; he was known for his sympathy for the nationalist aspirations of the Indians but not for those of other Jews. As the only Jewish member of George’s cabinet, Montagu participated in a public anti-Zionist statement asserting that Zionism “regards all the Jewish communities of the world as constituting one homeless nationality,” a notion that the statement “strongly and energetically protests.” Zionism, argued the statement, “must have the effect of stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands.”

There were prominent British Jews favorable to the Zionist project, including Montagu’s cousin Herbert Samuel. Yet as the British writer Chaim Bermant notes, Montagu was a “particularly formidable opponent, arguing both from the standpoint of the assimilated Jew and as Secretary of State for India.” If the efforts of Montagu were ultimately in vain, it was because the most politically powerful Jew in England was foiled by the most politically powerful Jew in America: Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.

Brandeis had been raised with no Judaism at all and for much of his life approached Zionism in the same manner as Montagu. In 1905, he informed a Jewish audience that there was no place in the United States for “hyphenated Americans,” adding as late as 1910 that “habits of living or of thought which tend to keep alive differences of origin or classify men according to the religious beliefs are inconsistent with the American ideal of brotherhood, and are disloyal.” Yet he did know of one Jew who clearly saw no contradiction between public Jewishness and patriotic Americanism. That was his mother’s brother, a lawyer by the name of Lewis Dembitz.

Like Brandeis, Dembitz lived in Louisville and was revered there for his achievements in the law and for the way he lived his life. Yet he was also admired by Gentiles for his dedication to Judaism. “Business and pleasure never interfered with the lawyer-scholar’s religious obligations,” a gushing obituary in the Louisville Courier Journalreflected, adding that “Mr. Dembitz’s doctrine prohibited work on the Sabbath day, and he never was known to violate the teaching.” Brandeis very much admired his uncle and changed his middle name from “David” to “Dembitz” in memory of the man who had helped shaped his choice of career.

In 1914, Brandeis was visited by Jacob de Haas, former secretary to Theodore Herzl, ostensibly to be interviewed about insurance law. De Haas offhandedly inquired whether Brandeis was related to a “noble Jew” by the name of Lewis Dembitz, who was an ardent Zionist. As the writer Rick Richman has documented, this meeting alerted Brandeis to the possibility that Zionism was not irreconcilable with Americanism. Thereupon he rose in Zionist leadership in America even as he was elevated by President Wilson to the Supreme Court in 1916. The following year, when Montagu made his opposition to the declaration known, Chaim Weizmann cabled Brandeis to ask “if President Wilson and yourself would support [the] text.” Brandeis, Richman writes,

wired Weizmann that, based on his talks with Wilson, the President was in “entire sympathy” with the draft declaration and in mid-October, Wilson himself passed a private message to the British supporting the declaration. It was issued two weeks later. The message was, Weizmann wrote later, “one of the most important individual factors” in breaking the deadlock. Nahum Goldman, later president of the World Zionist Organization, wrote in his autobiography that without Brandeis’s efforts, the Balfour Declaration “would probably never have been issued.”

Yet issued it was, and Montagu was crushed. “It seems strange,” he reflected, “to be a member of a government which goes out of its way, as I think, for no conceivable purpose that I can see, to deal this blow at a colleague that is doing his best to be loyal to them, despite his opposition. The government has dealt an irreparable blow to Jewish Britons and they have endeavored to set up a people which does not exist.”

The irony—or perhaps the providential nature—of this moment is difficult to miss. One of the most important Jews in England had done all he could to deny Jewish peoplehood, only to be foiled by one of the most important Jews in America, who had only just ceased to think about his own Jewishness in the exact same way.

Montagu died in 1924, at the age of 45, never achieving the apex of political power, and with his assault on Zionism a failure. Yet Montagu’s legacy lives on in the many Jews today who seem concerned for the nationalist aspirations of all other peoples except their own, and who raise the specter of dual loyalty. In this, Montagu brings to mind the criticism of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, who once wrote that the “emancipated modern Jew has been trying, for a long time, to do away with this twofold responsibility…the universal and the covenantal, which, in his opinion, are mutually exclusive.” This was true in the age of Edwin Montagu, and, alas, it remains true today.

Meanwhile, Dembitz may be as unknown as Montagu, if not more so. But one can rightly say that millions of Jews enjoy the fruits of his labor and his life, every day, in a vibrant and miraculous Jewish state. It is important that his legacy inspire Jewish Americans, that we be known for our dedication to this country and simultaneously for exercising our freedoms in defense of Jews, and in dedicated observance of the faith of our fathers. If we do so with integrity, we cannot fully imagine the extraordinary fruits that our lives, like that of Dembitz, might bear. May the memory of Lewis Dembitz be a blessing. On November 2, may we honor the full legacy of the man as we mark the hundredth anniversary of a day that his life helped bring about.

This essay was originally published in Commentary.

Lewis Dembitz and the Balfour Declaration.